-

Details

- Other Title

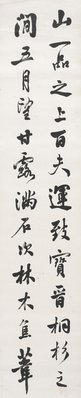

- [Four scroll set]

- Place where the work was made

-

China

- Media categories

- Scroll , Calligraphy

- Materials used

- four hanging scrolls; ink on paper

- Dimensions

-

a - right scroll, 1582 x 333 cm, image

a - right scroll, 192.5 x 39.5 cm, scroll

b - centre right scroll, 1582 x 333 cm, image

b - centre right scroll, 192.5 x 39.5 cm, scroll

c - centre left scroll, 158.2 x 33.3 cm, image

c - centre left scroll, 192.5 x 39.5 cm, scroll

d - left scroll, 158.2 x 33.3 cm, image

d - left scroll, 192.5 x 39.5 cm, scroll

- Signature & date

Signed c.l. part d, in Chinese, inscribed in black ink "... Chen Botao".

Signed l.l. part d, in Chinese, stamped in red ink “Botao zhiyin [artist's seal]".

Signed l.l. part d, in Chinese, stamped in red ink “Meihuacun zhuren [artist's seal]".

Not dated.- Credit

- Gift of Dr. James Hayes 2003

- Location

- Not on display

- Accession number

- 291.2003.a-d

- Copyright

- Artist information

-

Chen Botao

Works in the collection

- Share

-

-

About

‘The residence is encircled by hundreds of wutong [Chinese parasol trees], willows, Chinese toons and China firs. They were fertilised with manure, so after ten years they grew into an enormous shady shelter; truly it could be called ‘a shaded abode’. During the late fourth moon, the woodcutter of Mount Shanghuang came to tell me there was an unusual rock. So I went there to have a look. The rock had eighty-one holes – the largest one resembled a bowl and the smallest one could only fit a finger. Its quality and features were superb. I employed a hundred workers to carry the rock down [the mountain] and relocated it in among the trees [surrounding my abode]. On the 15th day of the 5th moon, pleasant dews which were as white as jade pearls, fell and covered the rock, trees and reeds. The district [officials] were trying to take it for themselves, and even to this day they still have not given up.’

Inscription and signature: Written for Dachu as he requested, Chen Botao.Chen Botao (alias Xianghua, style name Zili) was a native of Dongguan in Guangdong province. At the age of 25, he took first place in the prefecture civil service examination, and in 1892 passed the metropolitan examination (‘tanhua’, third place) and was granted the position of compiler at the Hanlin Academy (1). He was appointed the chief examiner for provincial examinations in Yunnan, Guizhou and Shandong. In 1906, he was sent by the court to Japan to investigate the Japanese education system. On his return, he was appointed educational administrator for Jiangsu province, and then deputy governor of the province. He retired to Guangdong in 1910, but in the following year when the republican revolution occurred, moved to Hong Kong and spent the rest of his life there devoting himself to scholarly research and calligraphy. A number of his remaining extant calligraphies are engraved on shrines, pavilions and even hospitals in the regions of Guangdong and Hong Kong.

Chen’s composition in these four hanging scrolls is taken from a letter written by the renowned Song dynasty painter and calligrapher Mi Fu (1051–1107), in which Mi, in a graceful and effortless style of running script, portrayed his charming residence at Dantu in present-day Jiangsu province. A comparison of the two works reveals that Chen had copied Mi’s style closely. In China, the traditional and most effective way of learning and practising calligraphy comprises a basic step: the ‘lin’ (close copy), in which a novice tries to reproduce an original work as meticulously as possible without the aid of tracing or mechanical means. By copying the model calligraphy, a practitioner learns to recognise structure, patterns and the style of the past masters. The practitioner then writes independently, developing his own style. Since Mi Fu was regarded as one of the most brilliantly inventive calligraphers in Chinese history, his works were mostly copied by those learning calligraphy. Like many established calligraphers, Chen Botao not only learnt his skill from his teachers Chen Li and Li Wentian, but also from a wide range of calligraphers of the past.

Notes

1. Hanlin Academy was an elite scholarly institution at court that performed secretarial, archival and literary tasks for the court and established the official interpretations of the Confucian Classics. By the time of the Qing dynasty, admittance was granted only to those who did exceptionally well in the 'jinshi' examination. Hanlin scholars functioned as the emperor’s close advisers and confidential secretaries.‘The Poetic Mandarin: Chinese Calligraphy from the James Hayes Collection’. pg.94.

© 2005 Art Gallery of New South Wales -

Places

Where the work was made

China

-

Exhibition history

Shown in 1 exhibition

The poetic mandarin: Chinese calligraphy from the James Hayes collection, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 23 Sep 2005–27 Nov 2005

-

Bibliography

Referenced in 1 publication

-

LIU Yang, The poetic mandarin: Chinese calligraphy from the James Hayes collection, Sydney, 2005, 94-95, 96-97 (illus.). cat.no. 25

-