Invisible friends

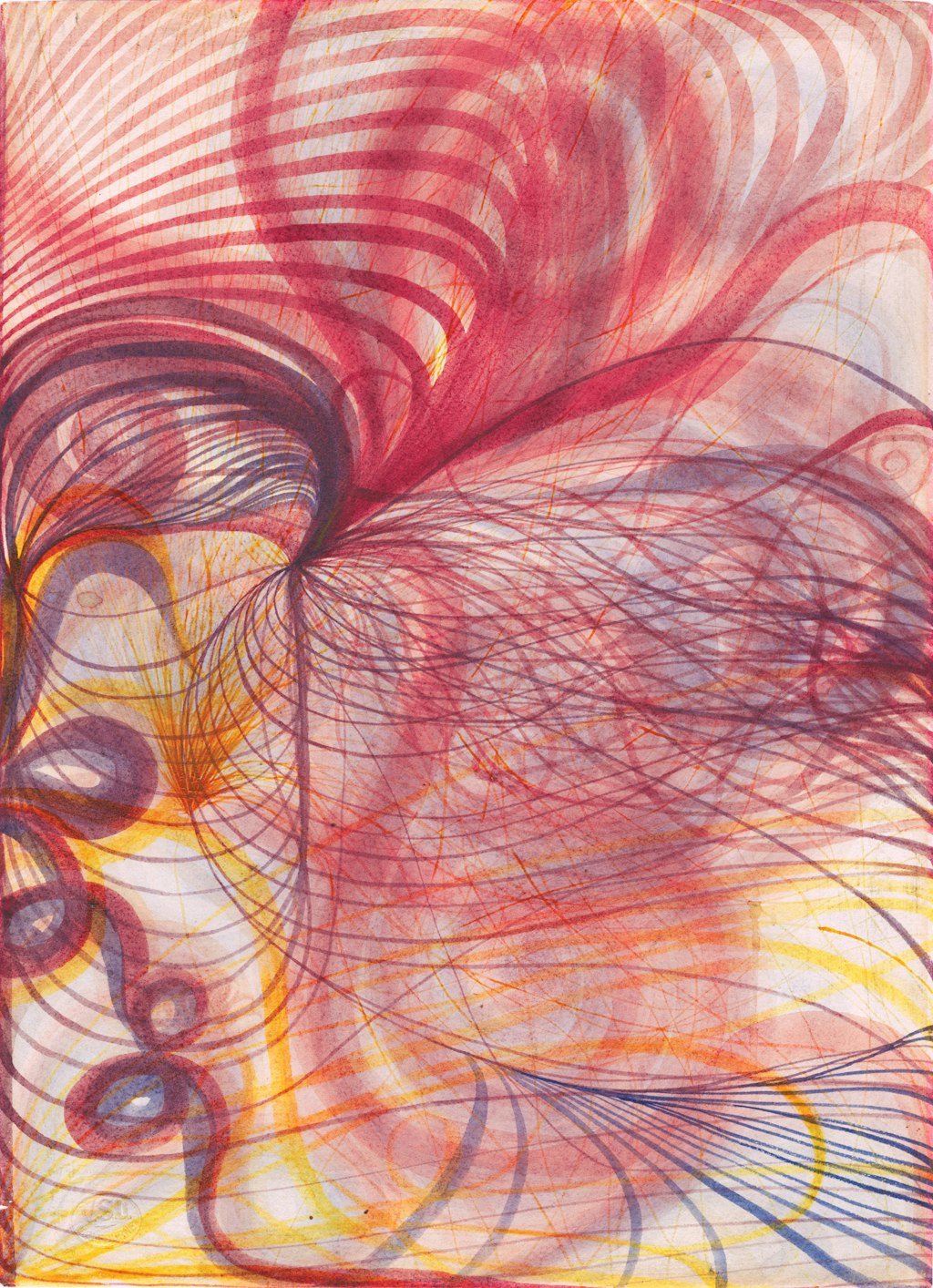

Georgiana Houghton The eye of God 1862, courtesy the Victorian Spiritualists’ Union Inc, Melbourne, Australia

I must explain that in the execution of the Drawings my hand has been entirely guided by Spirits, no idea being formed in my own mind as to what was going to be produced, nor did I know, when a stroke was commenced, whether it would be carried upwards or downwards …

Asked to imagine the watercolours of a middle-aged, middle-class woman living in Victorian-era England, one might well conjure a sentimental portrait, perhaps a floral subject in quiet pastels declaring the close observational powers of its demure creator. But in the 1860s and 1870s, one woman fitting that description created such surprisingly radical, ostensibly abstract artworks that they even astounded their maker; ‘works of art’, she once declared ‘without parallel in the world.’

Still, Georgiana Houghton (1814–84) did not create her astonishing works alone: her hand was guided by the spirits she called her ‘invisible friends’ – long-dead artists, family, friends and angels – who, through her, created the intricate, swirling, mesmeric watercolour drawings to be shown at the Art Gallery of New South Wales from 4 November 2023 to 10 March 2024.

Houghton was born in Las Palmas in the Canary Islands, with Scottish ancestry on the maternal side of her family (she delightfully posits that both ‘circumstances’ contributed to her ‘receptivity for spiritual gifts’). Growing up mostly in London, Houghton lived an ordinary, if devout, Anglican life with her parents and at least ten siblings, many of whom were to die young. The death of one of those siblings, her beloved sister Zilla, hit Houghton especially hard. Like many of her generation who had witnessed so much death within a culture that ritualised and elevated mourning, she looked to spiritualism for solace.

It would be hard to overstate the impact and reach spiritualism had in 19th-century life and culture. Emerging first in America, spiritualism was in part a reaction to the deadly devastation of the civil war, and in part to unprecedented social, scientific and religious revolutions. At its simplest, it was (and continues to be) a belief system centred around communication with spirits of the dead. Fired by a reaction to rationalist, scientific, dogmatic Christianity and patriarchal culture, it would become a major vehicle for the spread of libertarian ideas in the mid-19th century including, not insignificantly, women’s rights. Women acting as free subjects leading an egalitarian movement became visible through public seances, mediumship and spirit drawing; routes that allowed them to earn incomes in ways previously unknown. The emergence of spiritualism also correlated with that of the professional female artist.

Attending her first séance in 1859, Houghton sought out and made contact with her sister Zilla. Houghton soon became a medium, then later a prominent figure of the spiritualist movement. She was elected to the council of the British National Association of Spiritualists and was a founding member of the later London Spiritualist Alliance (today the College of Psychic Studies).

She was also a trained artist. Houghton likely received her ‘earthly training’, as she called it, in France, saying of drawing that she ‘devoted the chief part of my life to that accomplishment.’ She had given up making art in 1851 after the death of Zilla, who was also an accomplished artist, when in 1861 she was introduced to the ‘fresh wonder’ of the spirit drawings of one Mrs Elizabeth Wilkinson. Stimulated again to make art that also helped her broadcast her spiritualist theology, Houghton was finally aided in achieving her artistic aims by connecting with her first spirit guide.

Houghton rapidly developed her two intertwined skillsets, as medium and artist. For her, painting became the way to express the connection between the visible world and the invisible spirit realm. Considering the ‘manifestation first, and art second,’ Houghton’s art would be inconceivable without her mediumship.

Georgiana Houghton The flower of Samuel Warrand 1862, courtesy of the Victorian Spiritualists’ Union Inc Melbourne, Australia

Georgiana Houghton The flower of Samuel Warrand 1862, courtesy of the Victorian Spiritualists’ Union Inc Melbourne, Australia

Beginning with spirit portraits in the form of the flowers she believed sprang up in the spirit realm on the birth of each child, Houghton soon moved away from direct representation. Where Mrs Wilkinson was perhaps the first artist to draw flowers as spirit portraits and provide a framework for understanding the images of other spiritualist artists such as Anna Mary Howitt and Houghton herself, her work remained exclusively figurative. Houghton’s, on the other hand, would develop to reflect her own intricate sacred symbology, with a radical new artistic language that heralded the nonobjective modernist abstraction to come.

As Houghton’s artistic reputation grew, she showed her drawings in weekly sessions in her home. In 1867, she displayed and spoke about her works for the inaugural meeting of the Spiritual Athenaeum, and in 1865 tried for display at both the Institute of Painters in Water Colours and the Royal Academy of Arts without success (though accepted at the RA, the works were never hung). Finally in 1871, Houghton set up her own exhibition. In a celebration of ten years of her drawing mediumship, she displayed her Spirit Drawings in Water Colours at the New British Gallery in Old Bond Street, London – framing and preparing them, producing pamphlets and advertisements as well as a catalogue (including a special pink edition she offered to Queen Victoria), and attending each day to speak with and instruct her many fascinated visitors.

The authorship of the drawings was attributed thus: ‘By Miss Houghton, through whose mediumship they have been executed.’ It was an acknowledgement of her working method of being ‘passively active,’ a phrase she adopted from the 17th-century French Quietist, Madame Guyon, as a way of thinking through her relationship to painting under guidance.

Houghton recognised in her creative output ‘works that could not be criticised according to any of the known and accepted canons of art.’ These were visionary works of sacred symbolism that adhered to her own complex colour system. In her catalogue she charted the symbolic ‘interpretation of colours’ given to her by the spirits: primary colours for the Holy Trinity of the Christian religion, and others derived from them expressing idiosyncratic meanings such as courage (cadmium), integrity (ultramarine), or a love of justice (burnt umber).

Responses to the exhibition were ambivalent, and it was both panned and applauded by visitors from the worlds of religion, science and the arts, who Houghton declared, ‘revelled in the glories of colour, the marvellous manipulation, the delicacies of delineation.’ It confounded and delighted but didn’t sell. Having spent all of the small legacy left to her by an aunt on its production, Houghton was left deeply in debt.

Of the 155 works she so proudly showed at the New British Gallery (and the likely many more she produced in her lifetime), today only 46 remain. The exhibition of 30 at the Art Gallery is the greatest number of these ever displayed together outside their unlikely home in the chapel of the Victorian Spiritualists’ Union in Melbourne.

Installation view of Georgiana Houghton: Invisible Friends at the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Georgiana Houghton: Invisible Friends joins the recent run of exhibitions exploring previously neglected female spiritualist artists, such as Hilma af Klint and Emma Kunz, for whom the creation of art is understood as relational, as an act of receiving and mediation. Unsanctioned and polyphonic, spiritualist mediumship unsettled the very foundations of modern life interrogated more directly by later modern artists. Years before theosophy and anthroposophy roused artists from Vasily Kandinsky to Clarice Beckett, the spiritualist mission took artists and mediums like Houghton to places where power relations and identity were not fixed. If often gently proclaimed, such a mission nonetheless had subversive and anti-authoritarian potential, and the exploration and expression of the invisible spirit realm exerted a profound influence on the artistic consciousness of the 20th and 21st centuries.

A version of this article first appeared in Look – the Gallery’s members magazine