Queering the collection

Discover juicy facts and queer stories behind the artworks, artists and their subjects in these works from the Art Gallery collection.

You can visit the artworks on a self-guided tour of the Grand Courts – compiled by our Library and Archive team – for Queer Art After Hours, presented with Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras on 2 March 2022.

Left to right: Dora Ohlfsen Woman with bear skin 1920; Frederic Leighton An athlete wrestling a python 1888–91; Apollo c1770

Dora Ohlfsen Woman with bear skin 1920

From 1902 onwards, Ballarat-born artist Dora Ohlfsen and her Russian partner Elena von Kügelgen lived in Italy, where Ohlfsen became an internationally successful sculptor. Woman with bear skin gives an insight into her skills, the Adelaide Register noting that ‘it has been said of [Ohlfsen’s] figures that they seem to “live,” so unerringly has she stamped them with individuality and charm’.

During the First World War, Ohlfsen worked on an Anzac medallion to be sold in aid of permanently disabled Australian and New Zealand veterans. (A cast of it can be seen in Brook Andrew’s Tombs of thought: fire installation, also on display in the Grand Courts.) After the Treaty of Versailles was signed, Ohlfsen brought the newly cast medallions to Australia for distribution. While in Sydney she also hoped to arrange for the completion of the bronze pane she had been commissioned to create for the Art Gallery of NSW entrance. As it was, Ohlfsen’s panel was never made but Wiradjuri artist Karla Dickens has been commissioned to produce a new panel, To see or not to see, to be installed later this year.

Frederic Leighton An athlete wrestling with a python 1888–91

In the golden age of the posed ‘tableau vivant’, an Australian body builder, Clarence Weber, made quite a career from live performances and picture postcards recreating famous statues of athletic male nudes. A photograph of Weber posing as Leighton’s Athlete wrestling with a python, taken around 1912, made its way to London where a leading physical culture advocate, Monte Saldo, published it in his book How to pose, identifying it as a photograph of Leighton’s model. Leighton in fact used Angelo Colarossi, a professional artist’s model who also posed for Albert Gilbert’s famous sculpture of the winged figure of Eros at London’s Piccadilly Circus. Weber wasn’t even born when the original bronze of the Athlete was cast and was a nine-year-old living in a bayside suburb of Melbourne when this marble version was carved.

Wallendorf Apollo c1770

As depicted in classical Greek culture, the sun god Apollo has characteristics that today might be considered non-binary. For example, although assigned a male identity, they are often depicted in ancient Greek pottery motifs wearing feminine clothes or accessories, such as veils or flowing robes. Apollo is said to have had affairs with men and women, and Niobe, Queen of Thebes, openly mocked the sun god’s effeminate appearance.

When Wallendorf pottery decided to craft a collection of porcelain mythological figures during the classical revival of the late 1700s, their Apollo figure was given a feminine appearance, especially when compared to the Wallendorf figure of the usually overtly masculine messenger god Mercury (on display nearby).

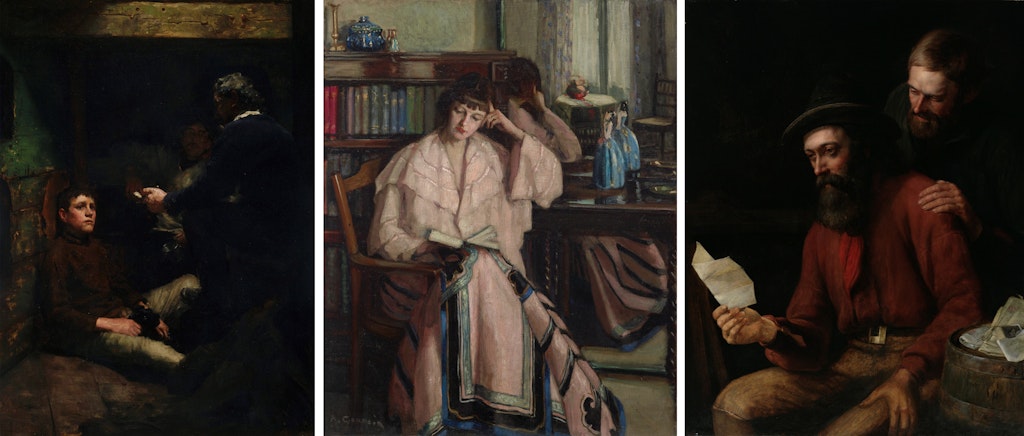

Left to right: Henry Scott Tuke A sailor’s yarn 1887; Agnes Goodsir Chinese skirt 1933; William Strutt (attrib) Gold diggers receiving a letter from home c1860

Henry Scott Tuke A sailor’s yarn 1887

Henry Scott Tuke was a prolific painter of the male figure. An enthusiastic nude bather, he was best known for his paintings of young men frolicking in the Cornish seaside. Based in Falmouth, Tuke painted A sailor’s yarn on board his newly acquired floating studio, an old French brigantine named Julie.

In 1889 the Illustrated Sydney News considered the Art Gallery’s new acquisition as ‘a work of some merit, [which] tells its story sufficiently, but it belongs rather to the class of “pot-boilers”’. The Sydney Morning Herald considered it ‘altogether a human and honest work … the artist has made every inch of the canvas help to tell the story’.

Agnes Goodsir The Chinese skirt 1933

Paris between the wars was, for the saddest of reasons, a particularly welcoming place for creative women. The city, brutally close to the Western Front, had lost a generation of men. Social life in the City of Light was an increasingly feminine affair, which made it easier for lesbian couples to live their lives publicly.

Bendigo-trained artist Agnes Goodsir lived with her American partner, Rachel ‘Cherry’ Dunn, in an apartment on the Rue de l’Odéon, in the heart of the ‘Latin Quarter’. Goodsir’s works, described by the Australasian newspaper in 1927 as ‘a galaxy of beautiful, and even more beautiful women, doing feminine things: taking morning tea, posing before a mirror, reading, wearing blue hats or Chinese shawls’, found the ideal model in Dunn, the inspiration for many of her partner’s portraits. Chinese skirt, painted in 1933, shows Dunn doing such ‘feminine things’ as posing in front of a mirror, reading a book, while dressed in a Chinese robe … and is that morning tea, reflected in the mirror?

William Strutt (attrib) Gold diggers receiving a letter from home c1860

The Australian gold rushes in the mid to late 1800s provided unexpected opportunities for queer people. For example, transgender people could begin a new life on the goldfields that was true to their identity, far away from the harsh judgment of family and neighbours. But there were risks. Exposure could come at a heavy cost. This was the case for Edward De Lacy Evans, a young Irishman who arrived in Melbourne in 1856 and mined the Victorian goldfields before settling down as a farm worker near Bendigo.

Evans married several times. According to the contemporary press, his ‘somewhat effeminate face and figure at times excited comment’ but this was largely dismissed until 1879 when Evans, having broken down over evidence of his wife’s infidelity, was medically examined and his assigned gender made public. Although Evans had a brief moment of fame, working on the travelling show circuit in an attempt to raise money to leave Australia, his mental health never recovered from the scandal and he died in Melbourne’s Immigrants’ Home in 1901.

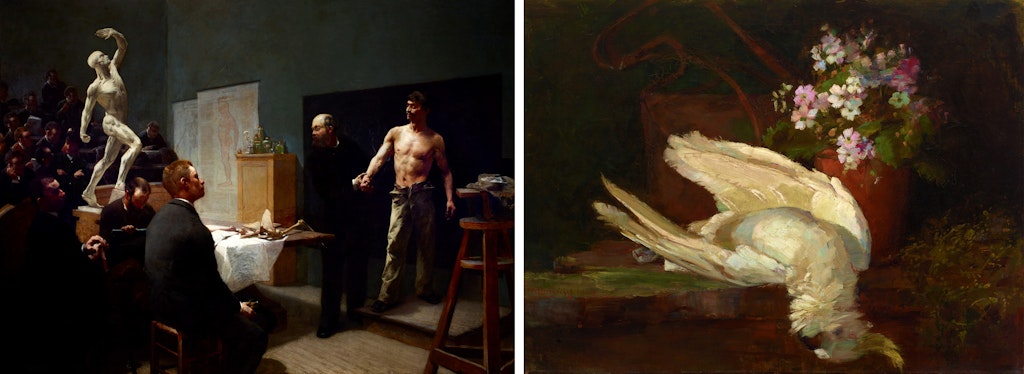

Left to right: Francois Salle The anatomy class at the École des beaux-arts 1888; Margaret Fleming The cockatoo 1895

Margaret Fleming The cockatoo 1895

Did you know that it was Graham Chapman, Monty Python’s openly gay member, who suggested changing a partially written sketch about trying to return a toaster to a disagreeable salesman into a sketch about trying to return a parrot?

Before the Art Gallery acquired this work from the inaugural NSW Society of Artists’ exhibition in 1895, the Sydney Mail had praised an earlier bird study by Fleming for its ‘neutral tints of the plumage delicately enforced in effective contrast’. Yet with this painting ‘the plumage don’t enter into it. It’s stone dead’. Perhaps the bird is, as the Monty Python skit so memorably put it, ‘tired and shagged out following a prolonged squawk’.

François Sallé The anatomy class at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts 1888

What breadth and simplicity. You don’t need a name for it; you know at once that it is an anatomy class. The great, cold bare room, the rows of students, and the sergent de ville in his cocked hat keeping order … But none of this obtrudes when you look upon the old professor and the subject of the demonstration. You see at once that though the professor has done this over and over again, it still has a fascination for him; he is full of enthusiasm as he demonstrates simply and emphatically the course and attachments of certain muscles, while the subject, used to the scene, complacently allows himself to be handled to illustrate the professor’s remarks. This is what indeed may be called an historical picture.

– Julian Ashton, Daily Telegraph, Sydney, 1 September 1906

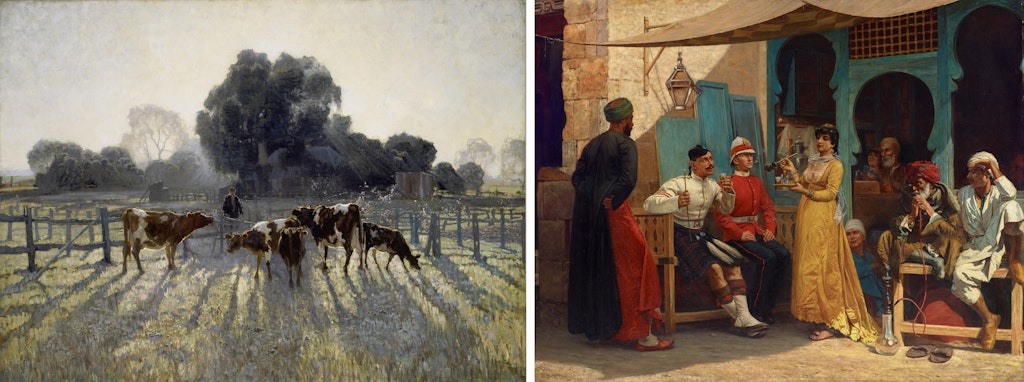

Left to right: Elioth Gruner Spring frost 1919; Walter Charles Horsley Great Britain in Egypt 1886

Elioth Gruner Spring frost 1919

Australian art history has tended to tilt strongly towards a narrow ideal of masculinity. For decades, any artist who strayed from the unironic celebration of the national manhood of bushrangers, Gallipoli diggers and cattle farmers could expect to be dismissed, often harshly, in the annals of Australian art criticism. So, even after Elioth Gruner established himself as one of the critics’ favourite landscape painters of early 20th-century Australia with works like Spring frost, his domestic situation, living openly with one, then two, male partners, couldn’t escape what we’d now call ‘queer coding’.

His landscape painting could be directly related to his service during the First World War, with critics noting that his work ‘was always completed, out of doors … even the rigours of a military camp in the last war could not affect his ardour’. But, at home in his Tamarama house which was ‘neat and shining and clean’, Gruner was ‘extremely fastidious’ about his decor and ‘very proud of his fuchsias’.

Walter Charles Horsley Great Britain in Egypt, 1886 1887

In Walter Charles Horsley’s Great Britain in Egypt, two British soldiers are taking tea in an Egyptian street. They have attracted the attention of the locals for their exotic uniforms. This is a reversal of the usual colonial practice of depicting the people of the taken lands as an exotic (and often erotic) ‘other’ – a practice that has been questioned in the work of many queer First Nations artists, including Brook Andrew, Karla Dickens and Kent Monkman, who are among the contemporary artists exhibited in the Grand Courts.

Kent Monkman The allegory of painting 2015

The title of this artwork recalls 17th-century paintings in which a female figure was used to personify ‘the art of painting’, despite the almost complete occlusion of women from the ranks of professional artists at the time. It especially invokes Artemisia Gentileschi, whose own take on the subject in 1638–39 took the form of a self-portrait. In Kent Monkman’s 21st-century version, it is his own gender-fluid alter-ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testikle, who assumes the role.

Monkman’s painting is a fastidious reprisal of a c1854 depiction of New York’s Shandaken Range by American painter Asher Durand. Durand’s colonial-era artwork portrays occupied land in the manner of a romantic European landscape, much like the 19th-century Australian paintings in the Grand Courts. Rich in art historical references, Monkman’s painting meditates on the place (and absence) of Indigenous and non-binary people in Western art history.

Kent Monkman The allegory of painting 2015 © Kent Monkman