Menu

Japan supernatural

2 Nov 2019 - 8 Mar 2020

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 'The old woman retrieves her arm' from the series 'New forms of thirty-six ghosts', 1889 (detail)

Welcome to 'Japan supernatural'.

Here you will encounter an astonishing parade of shapeshifting animals, fiendish imps, legendary monsters and ethereal spirits. Tales of these creatures have been told for centuries in Japan, with artists helping to make otherwise unseen worlds tangible.

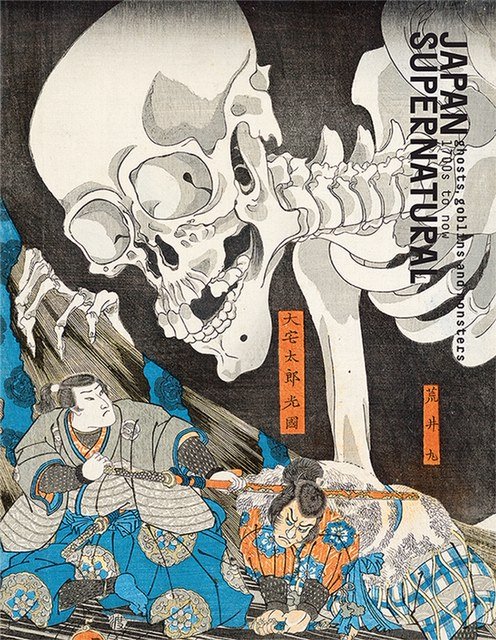

Japan Supernatural $45.00 AUD

Gallery shop

Kawanabe Kyōsai, 'Demon with a Buddhist prayer (Oni no nenbutsu)’, 1864

About the Japan supernatural exhibition

This exhibition introduces representations of the stories, events and beings of the invisible realm over almost 300 years, from the Edo period (1603–1868) to the present. Known by many names over time, supernatural beings are most often described as yōkai, while ghosts are called yūrei. Some yōkai are monstrous, others take human or animal form, and many are objects that have come to life. Such mystical creatures add richness and wonder to daily life and help to explain unusual events and experiences.

Yōkai and Yūrei

A wild array of supernatural creatures and beings from Japanese folklore

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 'The old woman retrieves her arm (Rōba kiwan o mochisaru zu)’, 1889

Utagawa Yoshimori, 'The tongue-cut sparrow (Shitakiri suzume)’, 1864

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 'Snow: Onoe Baikō V as Iwakura Sōgen (Yuki Onoe Baikō Iwakura Sōgen)’, 1890

Ukiyo-e artists

Legendary artists of the ‘floating world’ in the Gallery’s collection

Kentaro Yoshida

Kentaro Yoshida is a Sydney-based artist, illustrator and designer. He grew up in a fishing village in Japan surrounded by stories of yōkai and other supernatural characters from Japanese legend. His four-part mural brings an array of yōkai to Sydney and right into the Gallery. In Kentaro’s wall paintings, the yōkai burst through the sandstone facade of the building and parade along its interior walls. Night procession of the hundred demons (Hyakki yagyō) is a centuries-old tale of magical animals and shapeshifting creatures engaged in wild festivities. Usually seen by lantern light, the spirited characters shown include a frog-like kappa, a female demon (hannya), a tanuki raccoon-dog riding an earth spider, a long-necked woman (rokurokubi) threading her way through the procession, and a lute (biwa) come to life. Kentaro’s painting is a brilliant celebration of the enduring enjoyment of the supernatural in Japanese art and culture.

These murals are on display in the Gallery’s entrance court and are presented in conjunction with Japan supernatural.

Kawanabe Kyōsai, 'Hell Courtesan (Jigoku-dayū)’, early–mid 1880s