Art Sets.

Sidney Nolan centenary

Print this setBy the Art Gallery of NSW

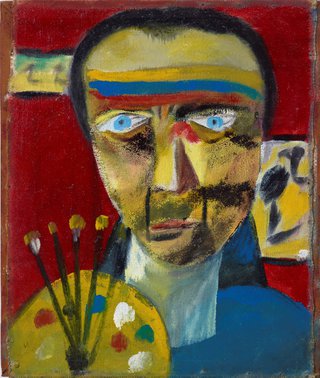

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan Self portrait 1943

In 1942 Nolan was drafted into the army and stationed in the Wimmera region of north-western Victoria. He countered the tedium of army life with a regime of reading and painting when able, resulting in a period of intense artistic questioning and experimentation.

In Self portrait Nolan wryly references his occupation as a soldier to tell of his ambitions as a modern painter. He imaged himself as an avant-garde warrior, brandishing his brushes and palette as his weaponry and his pigments as his war paint. He stands guarding his Wimmera landscape paintings that hang behind, suggesting the artist defending the cause of his modern creativity.

Described by Nolan as ‘rough as bags’, his raw portrayal and faux-naive style is indebted to his interest in outsider art and influence of works by Henri Rousseau and Pablo Picasso. Nolan had also started testing the expressive potential of Ripolin paint. Self portrait is telling of how he seized on the enamel’s flat, saturated finish to augment the intensity of his imagery.

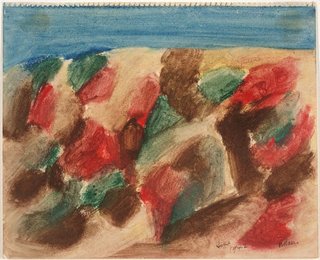

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan Dimboola landscape 1942

Drafted into the army in 1942, Nolan was moved to Dimboola on the Wimmera plains in mid October 1942 following his promotion to corporal.

Nolan’s enforced period in the seemingly featureless Wimmera flatlands encouraged him to grapple with the nature of the landscape before him, incorporating the subject into his continuing experimentations with form.

The small pastels Untitled (Wimmera landscape), Landscape and Dimboola landscape were among a number made in front of the subject or soon after, from memory.

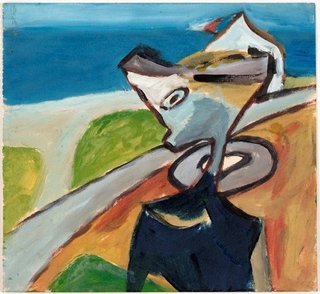

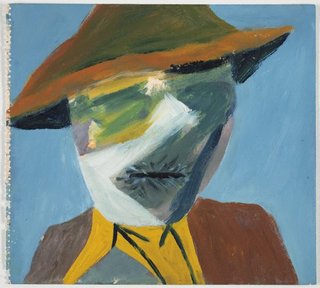

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan Farmer, Dimboola 1942

Inspired by the writings of Sigmund Freud and Melbourne psychiatrist Reg Ellery, Nolan worked on a series of surrealist-inspired figures while stationed at Dimboola which powerfully channel a sense of war-time menace.

Nostalgia for the sky and Farmer, Dimboola are from Nolan’s Dimboola sketchbook. These strange characters – an upward-gazing, feline-like devilish figure and local farmer whose features appear inverted by old age – reveal how Nolan created psychological, rather than specific, portraits of the people he encountered in the Wimmera.

Nolan had previously used Dulux for painting, a household gloss paint based on a plastic medium called alkyd. When looking for paint in the local Dimboola hardware shop in 1942, Dulux was his first choice and used for the work in his notebook.

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan Boy in township 1943

This was... done in the Wimmera; you can see in it a clear indication of what was to come, since it was done three of four years before Kelly was thought of... by me... and you see there a complete Kelly helmet in the windows of the burnt-out schoolhouses. - Sydney Nolan 1978

Boy in township is a composite image. Originally painted as a vertical landscape of a grass fire at Dimboola where he was stationed in the army, Nolan later reoriented the composition and added figure of the tilting boy who appears uneasy in his surrounds. Merging elements of the Wimmera plains with the St Kilda subjects that recall his childhood, Nolan refers to the emotional life of the past inhabiting the present.

Nolan’s subsequent remarks on this work reveal the makings of the iconography of his Kelly helmet.

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan Luna Park 1941

I remember as a kid going to sleep feeling the ratchet sound of the Big Dipper going ‘click, click, click’ and the screams of the girls and I’d go to sleep and think, well, I just wish I was up there with them… - Sidney Nolan 1977

Nolan grew up in the Melbourne beachside suburb of St Kilda, a popular weekend destination with a Luna Park fairground, swimming baths and a long promenading pier. Nolan held a lifetime affection for Luna Park. Encircled by two wooden rollercoasters; the Scenic Railway and the Big Dipper, Luna Park had a distinctive circular perimeter of uprights and cross-beams which found reference in many of Nolan’s early abstract images.

Luna Park reveals Nolan’s early efforts to create a modernist language out of private associations, rather than merely replicating the forms of the European avant-garde.

Luna Park is painted with nitrocellulose lacquer, a fast-drying gloss paint developed in the 1920s as a paint for cars, then signage, advertising and furniture. The most common brand of nitrocellulose paint was Duco which Nolan used extensively in his work as an artisan painter of props for the display of men’s hats for the Fayrefield Hat company between 1933 and 1939. In Luna Park, he utilised the bright, intense palette that the lacquer offered to recount the vivid fairground mood.

Uploaded image

Sidney Nolan Giggle Palace 1945. On loan from the Nelson Meers Foundation

Luna Park in Melbourne was part of my kitsch heaven as a boy. After I left the army, like a lot of others, I tried to recapture things, to see things again, to re-experience them. - Sidney Nolan 1978

Nolan grew up in the Melbourne beachside suburb of St Kilda, a popular weekend destination with a Luna Park fairground, swimming baths and long promenade. In Giggle Palace, he invokes childhood memories of Luna Park, picturing himself with his parents in front of a painted beachside backdrop in a sideshow photographer's studio. Nolan drew on the ambiguity and visual pun of this 'painting within a painting' that too suggests the funfair's play on reality and illusion.

The work was painted at a time when Nolan was in hiding after having deserted the army, and his memories of childhood pleasures seemed to serve as a creative antidote to his present traumas. His Ripolin-enriched palette and faux-naive style imbue Giggle Palace with the dream-like quality of childhood visions.

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan Island 1947

Island belongs to a series of paintings in which Nolan merges experiences of his two trips to Fraser Island in 1947 with the legends, histories and geographies of its landscapes.

Nolan had become fascinated by the legend of Eliza Fraser, the sole survivor of an 1836 shipwreck who was led back to settlement by escaped convict David Bracefell. When they reached the mainland Eliza cheated Bracefell by reporting him to the authorities, despite promising to seek his pardon for her rescue.

On his second visit to Fraser Island in October, Nolan - equipped with a plumber’s bag stocked with Ripolin-filled canteens - painted 12 works, including Island, on Masonite board that he had stripped from an abandoned army building. The figure in Island was based on a forester that Nolan had met and stayed with on the island. However, the meaning of the figure is elusive and can be read in relation to Bracefell. The man could also be an allegorical depiction of Nolan’s brother who drowned in Queensland in 1945, or potentially Nolan himself, who often identified with the forsaken figures in his pictures.

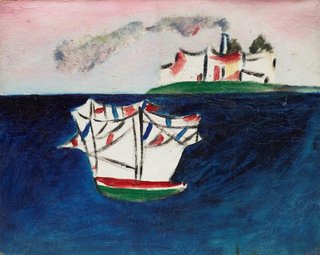

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan Untitled (St Kilda) circa 1943

Untitled (St Kilda) belongs to an extended series of works Nolan produced in the early 1940s based on the beachside suburb of his childhood. Unlike the relaxed atmosphere of other works of this series, the galleon-like ships and billowing smoke from the distant shoreline implies a battleground.

Nolan developed the image from actual events off the coast of Sulawesi in Indonesia (formerly the Dutch East Indies) in February 1942 when an allied fleet unsuccessfully attempted to prevent a Japanese landing at Makassar. In June 1943 he wrote to Sunday Reed, ‘[this is] something that always comes up when I think of boats and ships fighting upon water’. The work suggest how the menace of war had impinged itself in Nolan’s mind, transforming the landscapes of his youth.

Outback and beyond

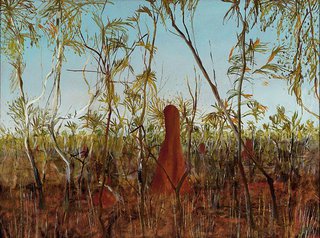

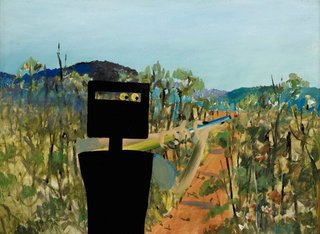

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan First-class marksman 1946

First-class marksman formed part of the original sequence of 26 paintings from Nolan’s first ‘Kelly’ series, painted between 1946 and 1947. Unlike the other works that were produced at John and Sunday Reed’s home Heide, First-class marksman was produced separately at artist Danila Vassilieff’s house – it has been displayed singly and as part of the original ensemble since 1948.

Nolan’s rendering of bushland entanglement and enigmatic portrayal of Kelly – armed, but not completely dangerous – results in one of his most engaging depictions of the bushranger. Kelly is depicted practising shooting at his hideout in the Wombat Ranges, recalling Nolan’s own training in the army between 1942 and 1944. The off-guard encounter with the protagonist distinguishes First-class marksman from the other works in this series.

With Kelly’s iconic black armour framing our view of the countryside, the work evocatively demonstrates Nolan’s merging of myth and history on our reading of place, and how human drama can augment our understanding of the landscape.

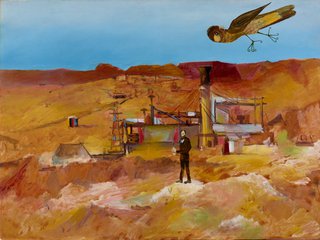

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan Pretty Polly Mine 1948

Nolan’s Pretty Polly Mine recounts his visit to a mine near Mount Isa in 1947. The mine manager liked feeding the birds every morning. Nolan drew on the incongruity and eccentricity of a dark-suited figure feeding the birds in such a setting. This, coupled with the large, deliberately out-of-proportion bird gives the painting a surreal quality and mimics the uneasy presence of Europeans in the Australian outback, a prevailing theme in much of Nolan’s work.

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan Central Australia 1950

In 1949 Nolan travelled with his wife Cynthia and daughter Jinx (Cynthia’s daughter who Nolan had formally adopted) through Central Australia. His encounter with the vastness of the centre had a profound impact on his practice.

In Central Australia, Nolan paints the exhilaration of expanse. He based the work on the dramatic topography of the interior, painting the primeval formations and saturated pigments of land and sky with a precision that it makes it appear dream-like. In doing so Nolan enhanced the landscape’s mystery, inscribing it with a modern sense of the sublime.

Nolan exhibited his Central Australia series to high acclaim at David Jones Gallery in 1950. Critic James Gleeson referred to the exhibition as ‘one of the most important events in the history of Australian art’. The seemingly infinite lunar-type formations of the land were a revelation and redefined white Australians’ perceptions of the nation’s landscapes.

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan Drought skeleton 1953

Death takes a curiously abstract pattern under these arid conditions. Carcasses of animals are preserved in strange shapes, which often have a kind of beauty or even grim elegance. - Sidney Nolan 1952

In June 1952 Nolan travelled to the Northern Territory and Queensland, commissioned by Brisbane’s The Courier-Mail newspaper, to record the effects of severe drought in the north of the continent.

Nolan’s drought images were influenced by a recent visit to Italy, where he had gained a similar sense of life suddenly suspended during a visit to Pompeii. The contorted forms of animals and humans petrified in the ashes following the eruption of Vesuvius in AD79 – of which he’d seen plaster casts in the museum there – bore strong similarities to the twisted yet still life-like limbs of carcasses that resulted from drought.

In Drought skeleton the last of the animal’s rotting flesh can be seen through the ribcage, painted in reds, browns and pinks, giving an unsettling impression of a fiery pit within.

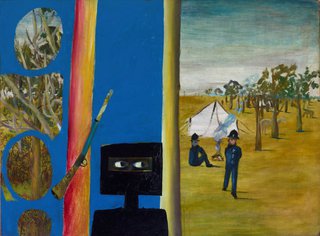

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan The camp 1946

The Kelly paintings are secretly about myself... From 1945 to 1947 there were emotional and complicated events in my own life. It’s an inner history of my own emotions - Sidney Nolan 1989

Nolan had deserted the army in 1944 and until 1948 lived in hiding, under the alias Robin Murray. During these years, the folklore of bushranger Ned Kelly gripped Nolan’s imagination. He read books, court records, police reports and press accounts on the history of the Kelly gang. He visited ‘Kelly Country’ in north-eastern Victoria, and the landscapes that had served as backdrop to the Kelly saga. Sharing an Irish ancestry, working-class roots and fugitive status with Kelly, Nolan had a sense of association with the outlaw that fueled his thinking. Merging personal symbolism with his impressions of Kelly’s history and countryside, Nolan created one of the most remarkable series in Australian art history.

The camp depicts Kelly’s reconnaissance on policemen sent to capture him, dead or alive, at Stringybark Creek. The bold division of the painting into two halves creates a powerful psychological tension: the calm landscape to the right is juxtaposed against an electric-blue area of paint, from which emerges the figure of Kelly, anxiously peering from the confines of his black armour as a silent, watchful presence in the landscape.

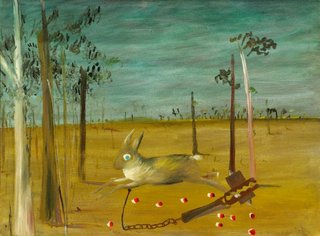

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan Drought 1953

The trip... has set me painting a big series of dead animals, the dried carcasses of horses, cattle, camels etc. It is a grim subject, but it has got me by the short hairs... Who knows who will buy them. I can’t honestly say they are drawing room paintings... - Sidney Nolan 1953

While Nolan was moved by the effects of drought that he witnessed in outback Australia, his resulting works were stark and unsentimental. The contorted, dessicated carcass became an icon – emphasised in the gold-tinged Drought 1953 – that signified for Nolan both an essential ‘Australian-ness’ and an intimation of apocalypse. The carcass reappeared in paintings, drawings and prints in which the various material qualities of his mediums brought nuanced variations on the theme.

AGNSW collection Sidney Nolan Kelly 1956

Nolan revisited the themes and subjects of his work throughout his career, reconsidering their imagery and meanings in new inventive formations. The black-helmeted Ned Kelly figure - one that Nolan claimed as an alter-ego - never left him but returned with different emphasis in a later series of paintings produced in England in the 1950s.

Nolan’s 1956 Kelly emerges in a dream-like landscape in somnambulistic guise. While the Kelly of Nolan’s initial series was figured as watchful, anxious and alert, his later dreaming Kelly is a figure of an intense introspection. Nolan’s palette has darkened, and while the landscape is non-specific, it seems far removed from the clarified light of his Australian Kelly subjects. As art historian Patrick McCaughey has observed ‘Nolan has transformed the local hero into a universal myth’.

Materials

Uploaded image