Art Sets.

John Brack

Print this setBy the Art Gallery of NSW

AGNSW collection John Brack The telephone box 1954

If I choose to paint the life I see around me, it is because I find people more interesting than things – John Brack, 1956

This painting brings us into claustrophobic proximity with a woman in a public telephone box. The tight framing of the work reinforces the figure’s constraint within the structure, while the angular rendering of her body and face emphasises her awkward posture as she strains to speak into the mouthpiece. The subject of the call is a mystery; the woman’s closed eyes deny us insight into her inner world despite the intimacy of the scene.

Brack has painted an urban neighbourhood with few trees and fewer amenities. His character is not fully dressed; the spiky clips tethering her hair would normally not be seen outside the home. Focused on her conversation, she is unselfconscious in the urgency of the moment, in which the act of communicating is presented as strained and isolating.

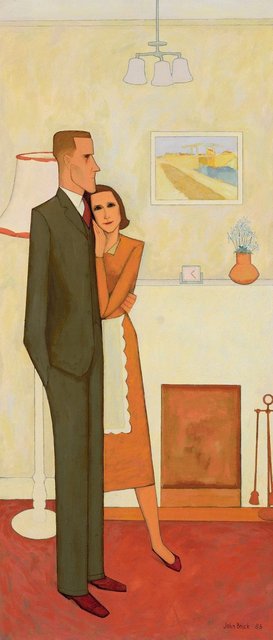

AGNSW collection John Brack The new house 1953

The new house was exhibited in John Brack’s first solo exhibition at Peter Bray Gallery, Melbourne in 1953. The subjects of the works in that exhibition were taken entirely from everyday life. In this painting a stoic male figure gazes into the distance, a sturdy pillar against which his wife leans lovingly. Her gaze engages directly with the viewer, inviting us to share her contentment in her recently acquired domestic stability – marriage and a new home. On the wall hangs a small colour reproduction of Vincent van Gogh’s painting The Langlois bridge (1888). This may be a reference to Brack’s discovery of art. Passing a shop in Little Collins Street, Melbourne as a 17-year-old, he had been struck by two small reproductions of Van Gogh paintings in the window. He later described it as ‘a sort of shuddering … overwhelmingly, (a) totally unexpected moment’ which prompted him to learn more about art, and eventually led to a life as an artist.

Brack’s vision of post-war Melbourne was not satirical, as some thought. Rather, it was empathetic and unjudgmental. This small slice of respectable suburban bliss would have been a salve to those who, less than a decade before, had experienced the privations and terrors of war.

AGNSW collection John Brack Barry Humphries in the character of Mrs Everage 1969

Brack’s preference for painting portraits of people he knew was challenged when actor and satirist Barry Humphries asked him to paint a portrait of his most famous – but fictional – character, Edna Everage. Brack refused, choosing instead to paint Humphries in character as Mrs Everage. For him, this was a subtle but important distinction. Brack saw himself working within a long tradition of art-making and many of his works allude to great historical paintings. Here he referenced the 18th-century portrait tradition of depicting women in character as literary, religious or mythological figures – in particular, British artist Joshua Reynolds’ painting of an actress, Mrs Siddons as the Tragic Muse 1783–84.

Barry Humphries in the character of Mrs Everage takes a couple of compositional cues from the Reynolds portrait, including voluminous drapery and outstretched arms, but here the comparison ends. Humphries’ cheeky gaze and over-the-top costuming remind us of his satirical intent in creating this outlandish character of post-war suburban respectability.

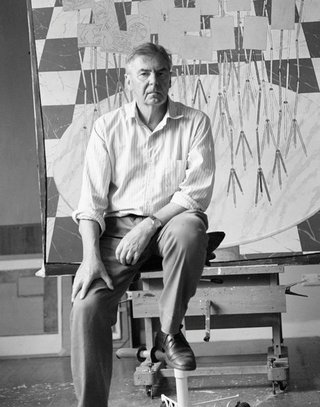

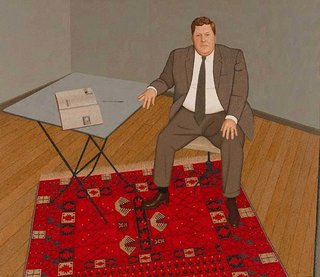

AGNSW collection John Brack Portrait of Fred Williams 1979-1980

My portraits are not simply a sort of photograph appearance of the subject … The portrait is not just the subject but what he means in the past, the present and the future – John Brack, 1965

Brack preferred to paint portraits of people he knew, so he might faithfully render their character and personality, as well as appearance. He painted his friend Fred Williams twice, first in 1958 and again more than 20 years later. The two met as students at the National Gallery School, Melbourne in 1946 and shared a studio for a couple of years, Brack painting by day and Williams by night. In his first portrait of Williams (which is now in the Art Gallery of South Australia), Brack depicted his friend close-up, leaning forward as if looking impatiently towards his future. In this second portrait (in the Art Gallery of NSW collection), Williams appears more relaxed, sitting comfortably, fingers pointed towards the diary in which he recorded his work. His authoritative presence and commanding pose reflects the respected position he held in the art world. The spindly table legs and revolving chair emphasise his bulk, lending Williams a monumentality that matched his confident self-possession as a mature painter and influence on his peers.

AGNSW collection John Brack Study for 'The bacon cutter shop no.1' 1955

In the early 1950s Australians witnessed media reports of atrocities committed during the recent world war, including images of victims of the Holocaust. These were a profound shock to many, including Brack. Although he had served during the war in Australia, he was not aware of the full extent of Nazi depravities until afterwards. The extremes to which human behaviour could lead soon became an important underlying theme in his paintings, although for many viewers and critics this was not immediately apparent. He made a small group of pictures of meat-slicing machines around this time. Contemporary viewers read them as unconventional but prosaic images of suburban life. In fact, Brack was referring to something far more profound and sinister. The sharp blades and clinical settings of these works have an air of disquieting potential for violence – the objects projecting a machine detachment from their devastating powers of destruction.

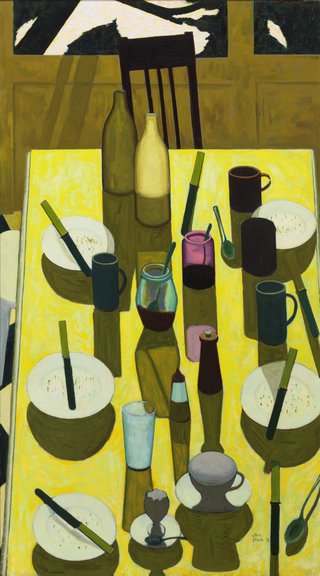

AGNSW collection John Brack The breakfast table 1958

This is the dining table of the Brack’s suburban Melbourne home, recently vacated by the family after breakfast. Lit by strong raking light, the objects – from milk bottles to toast crumbs – cast long shadows across the neon yellow tabletop, suggesting the passing of time in the ascent of the morning sun.

Brack was interested in the formal possibilities of composition and colour in making a painting. His placement of objects on the table and choice of an unusual aerial perspective bring the viewer into an enveloping and intimate proximity to an otherwise private domestic scene.

Combining the genre of still life with a commitment to painting his immediate environment, this work refers to the artist’s everyday life. By the time The breakfast table was painted, Brack and his wife Helen had four young daughters whose individual presence is implied here by the discarded tableware and breakfast scraps, left for someone else to clean up.

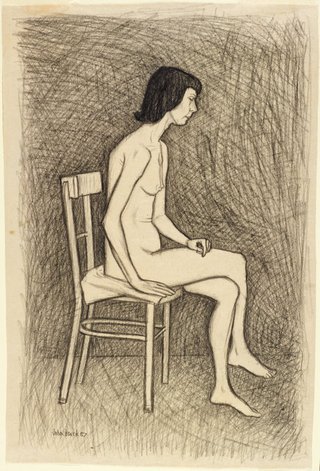

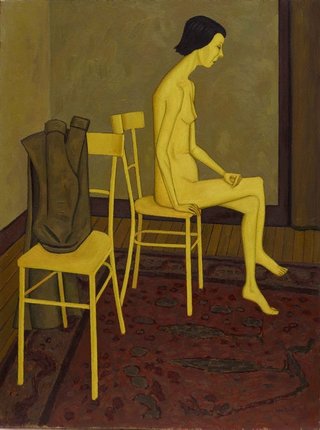

AGNSW collection John Brack Nude with two chairs 1957

In 1957 Brack advertised in a newspaper for a model, with the intention of painting a series of nudes. He had one response, from a thin, dark-haired, middle-aged woman who became the subject of a series of paintings and drawings made at the artist’s home in suburban Melbourne. In this series of nudes, Brack’s intention was to subvert popular expectations of the genre by de-eroticising his subject. In this painting she is seated on a simple wooden chair atop a Persian rug on a wooden floor, a motif that was to recur frequently in Brack’s nudes and interiors. A drab brown coat takes on a strange biomorphic form as it rests on an adjoining chair. Apart from these spare features, the room feels stark and empty. In removing any extraneous details of domestic life from his image, Brack offered no clues to the personality of his sitter. The yellow tinge shared by both figure and chairs gives a strange, unnatural cast and sense of uneasy tension to the scene. This, combined with the model’s closed eyes and pose turned away from the viewer, emphasises her alienation and isolation from the world around her.

AGNSW collection John Brack Head and arms (Barbara Blackman) 1954

Of all (the artist’s) devices, drawing is the chief, the only one that cannot be dispensed with. – John Brack, 1957

Barbara Blackman – poet, music patron and muse – modelled for a number of artists in 1950s Melbourne including her husband Charles Blackman, Joy Hester and both John and Helen Brack. This drawing was made using one of Brack’s favoured mediums, conté crayon, but differs from many of his other drawings of the 1950s in the loose, expressive quality of its execution. This suggests it was made quickly and with confidence for its own sake, rather than as a carefully considered composition destined to be developed into a painting – such as the drawing Study for ‘Nude with two chairs’ no 2.

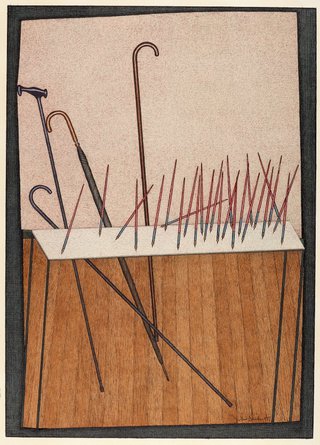

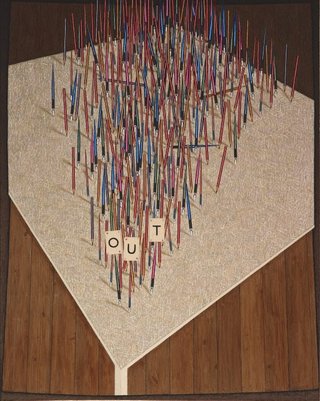

AGNSW collection John Brack Out 1979

In the 1970s, Brack moved away from explicit images of people towards the arrangement of inanimate objects in carefully constructed tableaux. He used items from his home or studio as models, including walking sticks, pens, pencils, playing cards, scalpels and wooden dummies. Painting with very fine brushes and aids such as stencils, he presented his models in elaborately staged, theatrical arrangements.

In this painting the sharp-nibbed pens and pencils are arrayed as a crowd marching relentlessly towards the edge, with more participants joining at the rear. Three of their number fall and are crushed as the crowd advances. The forward tilt of the table surface and irregular painted border just within the frame imparts a sense of imbalance and emphasises the illusionistic nature of painting itself. While devoid of the human figure, these late works are entirely about people; specifically, our complex social relationships and compulsion to belong, and how these forces manifest themselves in culture and society. The passing of history and the cyclical nature of life, as each new generation replaces the one before it, is implicit as Brack ponders the universal human behaviours that shape civilisations.

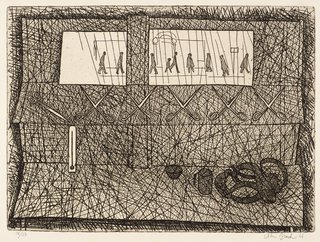

AGNSW collection John Brack Mirrors and scissors 1966

Shop window displays – including those of a local commercial kitchen supplier and a medical equipment store – became a key subject for Brack in the 1960s. They inspired a series of paintings and prints of banal or ambiguous forms such as scissors and kitchenware in theatrical window settings. Included among these works was his ‘surgical series’ featuring etchings of prosthetic limbs and surgical tools. An occasional human figure can be seen reflected in a mirror or glass, paradoxically separate yet enmeshed with the objects behind the window. Brack used compositional tools such as receding pictorial space, reflection and shadow to suggest ambiguity and multiple meanings. These works challenged the conventional genre of still life. In Brack’s quest to express the many facets of human experience, he considered the success of any picture to be dependent on the complexity of meaning it contained. Inanimate objects were to become an increasingly common motif in his work over the years, as simple still-life compositions evolved into active scenarios in which anthropomorphised objects perform allegories of human behaviour.

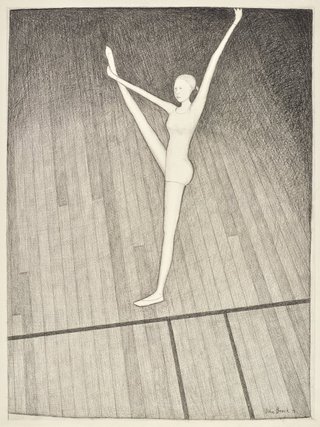

AGNSW collection John Brack In the corner 1973

Brack first made paintings of children in the late 1950s, when his four daughters were young, and returned to the subject in the early 1970s with a series of images of adolescents engaged in gymnastics. Testing the abilities of their bodies in parallel or competition with each other, the children’s elongated limbs and thin, underdeveloped bodies strain as they seek to build physical strength and mastery of their sport in their rituals of childhood play. Brack was interested in the cycle of life and found transitional stages such as adolescence enigmatic and unknowable to him, an adult.

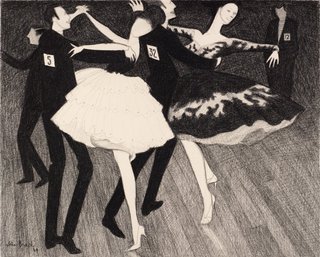

AGNSW collection John Brack Sketch for 'Latin American grand final' 1969

In 1969, Brack embarked on a series of paintings on the subject of ballroom dancing, a sport subject to a highly regulated set of rules and conventions. Brack planned and researched the series for at least two years, including taking a subscription to The Australian Dancing Times. This magazine published images from dance competitions which Brack used as source material for his compositions, often down to the details of the competitors’ identification numbers. The paintings’ reduced palette of bright pinks and yellows emphasises the highly stylised forms and rituals of ballroom dancing, including the rigid facial expressions of the dancers and their exaggerated yet precise movements and gestures. In this drawing and its related painting (now in the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra), Brack inserted a personal touch with a self-portrait – the solitary figure to the left of the composition. Brack considered the ballroom-dancing works to be visual metaphors for human interdependence – our relationships with each other, our struggle for individuality, and the performances we execute to fit in, and flourish, in society.

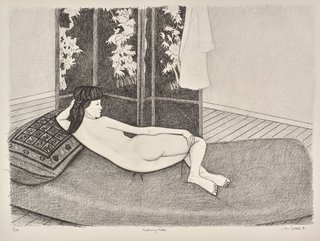

AGNSW collection John Brack Reclining nude 1981

When I paint a woman, I am not interested in how she looks sitting in the studio, but in how she looks at all times, in all lights, what she looked like before and what she is going to look like, what she thinks, hopes, believes and dreams. – John Brack

The female nude was a longstanding motif in Brack’s work, representing an ideal genre in which he could consider themes including the passing of time and the cycle of life. He also enjoyed the discipline of drawing from the live model, which he practised over the decades to keep his eye and hand ‘in trim’. Brack made a large number of paintings, drawings and lithographs depicting the nude posed in spartan and confined studio environments featuring sloping wooden floors and minimal, functional furnishings. Persian carpets were often included to symbolise human civilisation and cultural traditions.

This lithograph and Nude on bed come from a significant oeuvre of prints produced by Brack over his career as a way of making his work more accessible. He tended to work in collaboration with custom printers and print studios, finding the technical production of print editions less interesting than the fact that they could be multiplied.