Ghosts of the Spanish flu

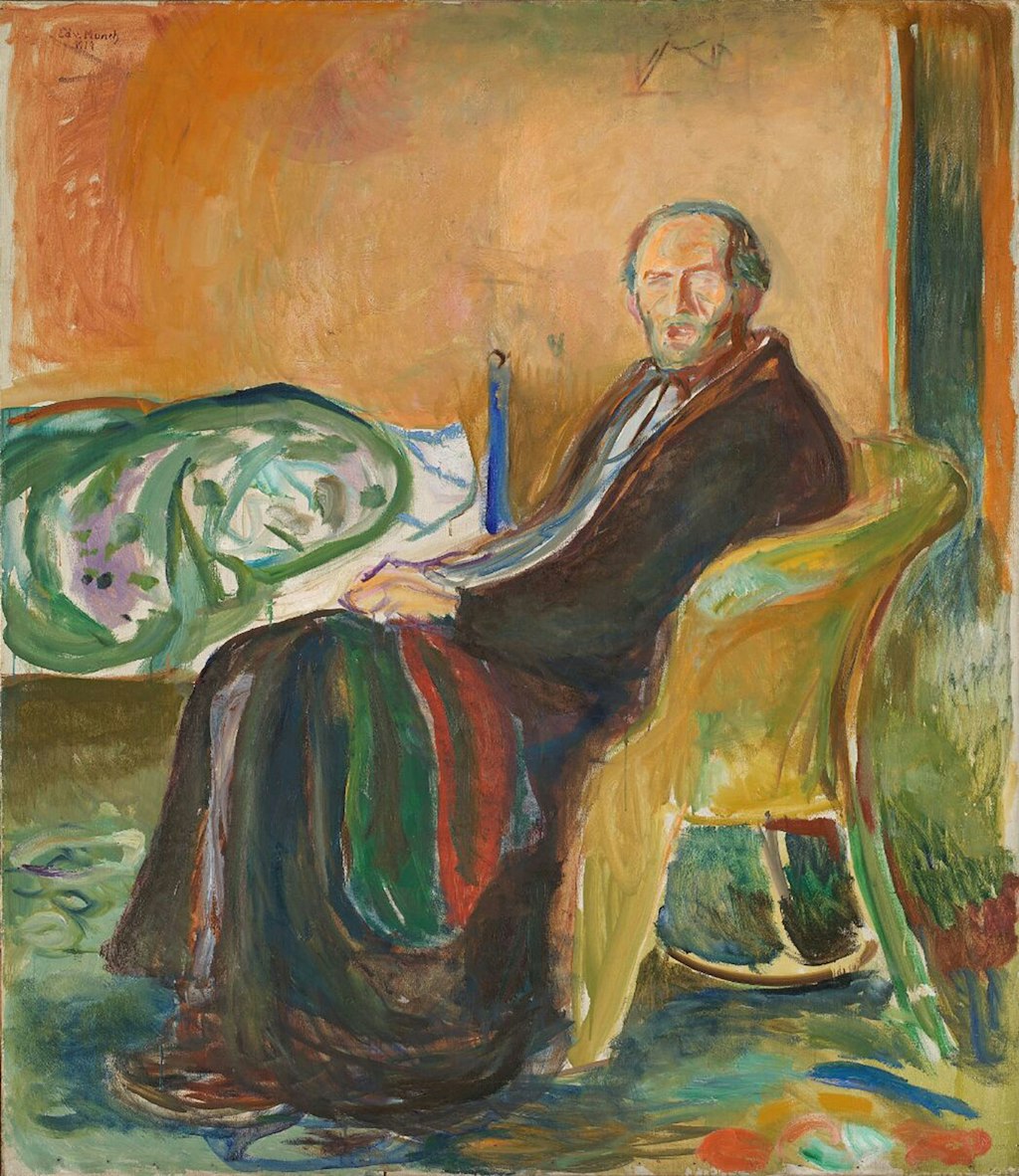

Edvard Munch Self-portrait with the Spanish flu 1919, National Museum, Norway. Photo: Nasjonalmuseet/Høstland, Børre, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution – Non-Commercial 4.0 International license

A once-in-a-hundred-year event. That’s how this coronavirus pandemic has been described. We have faced several pandemics over the course of the past century, but the global magnitude of this crisis is most often compared to the influenza pandemic of 1918–19. When that deadly and unprecedented strain of influenza tore through communities the world over, it claimed anywhere between 17 and 100 million lives. The data is sketchy. The world was at war and information was classified. It became popularly and unfairly known as the ‘Spanish flu’, but the true origins of the virus remain unknown.

As in our globally connected world, the mass movement of people helped move the disease swiftly across borders – a result of the demobilisation of troops as the First World War concluded. Around a quarter of the world’s population became infected. That got me wondering. With few households untouched by the effects of that virus and its ramifications, how did artists respond to the situation? If art is a mirror of society, would I find depictions of the overflowing hospitals and the unemployed – perhaps echoes of our current newsfeeds?

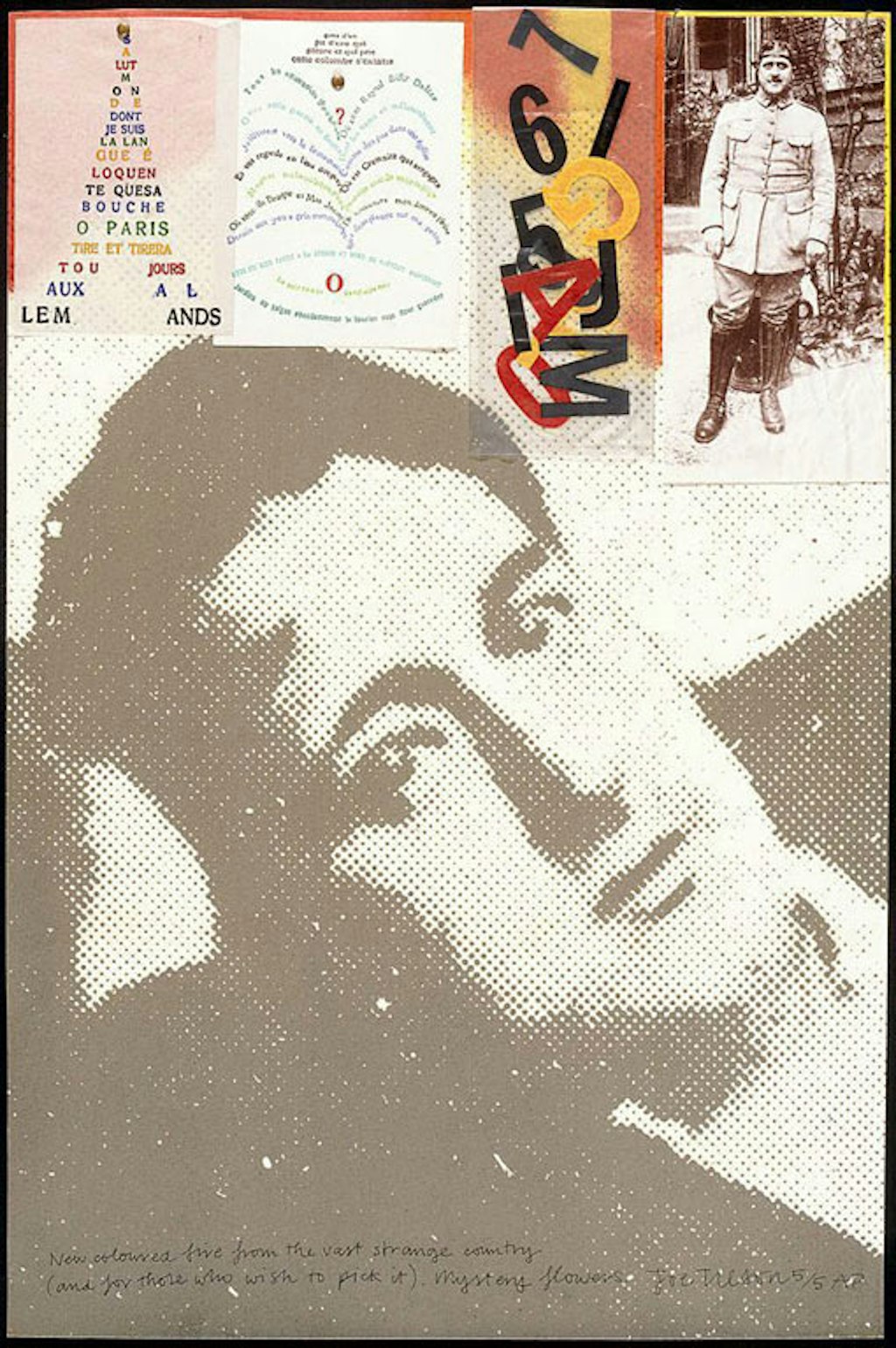

Joe Tilson G - Guillaume Apollinaire 1969-70, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Joe Tilson/DACS. Licensed by Copyright Agency

Joe Tilson G - Guillaume Apollinaire 1969-70, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Joe Tilson/DACS. Licensed by Copyright Agency

To my surprise, I discovered that few artists portrayed the events that unfolded. Laura Spinney suggests in her 2017 book Pale rider: the Spanish flu of 1918 and how it changed the world that this was because people were eager to move on from the spectre of death and dread after four gruelling years of war.

The death of Parisian art-world luminary Guillaume Apollinaire illustrates her point. The poet and art critic who coined the terms ‘cubism’, ‘surrealism’ and ‘orphism’ died from influenza on 9 November 1918, two days before Allied forces and Germany signed an armistice to end the conflict. Fellow poet Blaise Cendrars remembered Apollinaire’s funeral cortège being ‘besieged by a crowd of noisy celebrants of the Armistice, men and women with arms waving, singing, dancing, kissing, shouting deliriously… It was fantastic, Paris celebrating. Apollinaire lost. I was full of melancholy. It was absurd.’ Yet Apollinaire was not forgotten, as seen in the Gallery’s pop art portrait by British artist Joe Tilson, created some five decades later, which shows the poet in his French military uniform. Having sustained a shrapnel wound to the head during service, Apollinaire was weakened and susceptible to the virus.

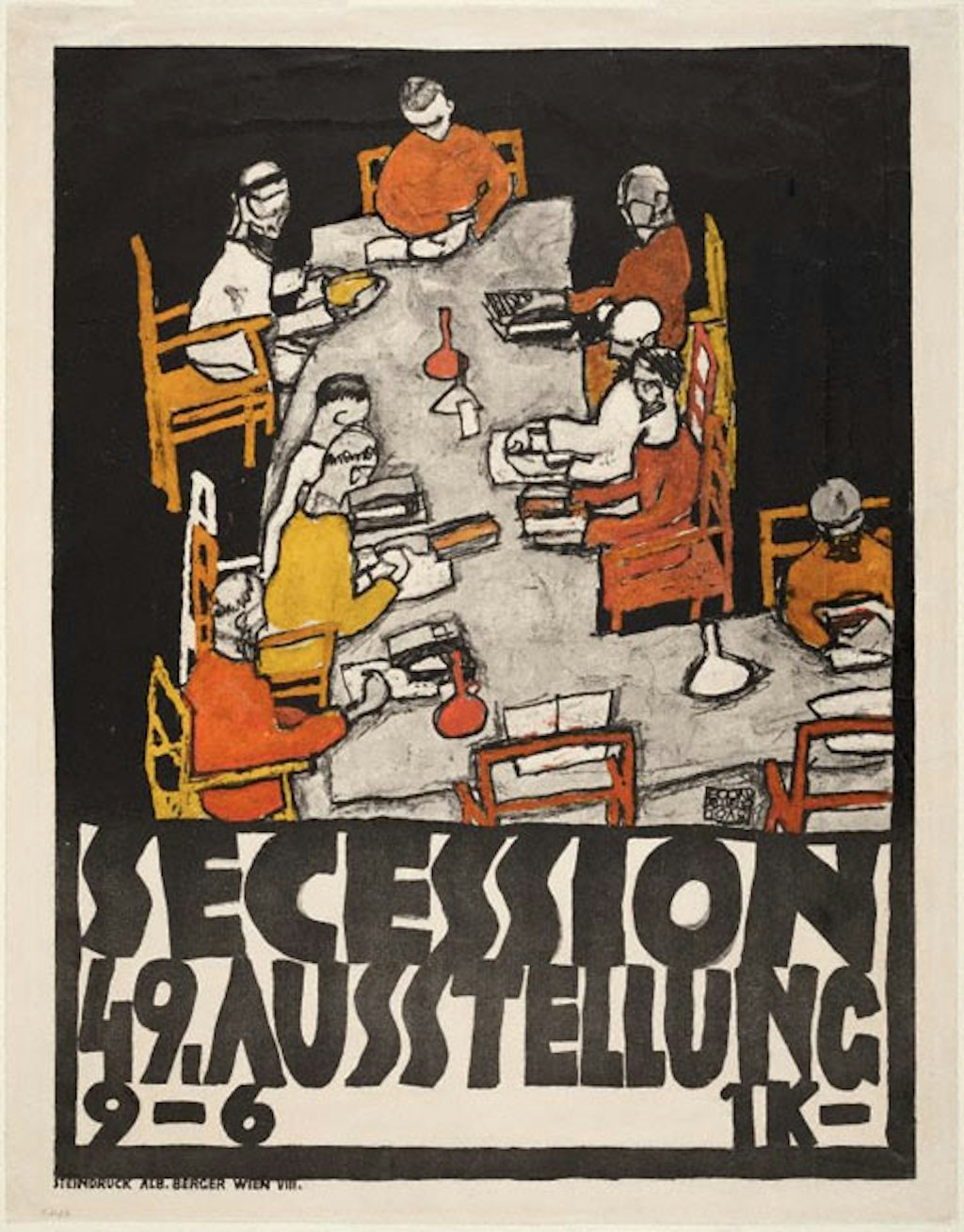

Egon Schiele Poster for the Vienna Secession 49th exhibition 1918, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Egon Schiele Poster for the Vienna Secession 49th exhibition 1918, Art Gallery of New South Wales

The Gallery’s collection holds further evidence of the devastation wrought by the Spanish flu, including works by Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt. Klimt, a founder of the Vienna Secession, had helped instigate the development of modern art in Austria. Schiele was his protégé, a wunderkind whose erotically charged art shocked Viennese society. Schiele’s poster for the 49th exhibition of the Secession group in March 1918 is reminiscent of the Last Supper, with Schiele seated Christ-like at the head of the table. In earlier versions, the empty chair opposite Schiele was occupied by his venerated mentor, but Klimt died of the flu in February and the seat was left vacant. By October, Schiele would also succumb, aged only 28. His final works are sketches of his pregnant wife Edith, who died three days before him.

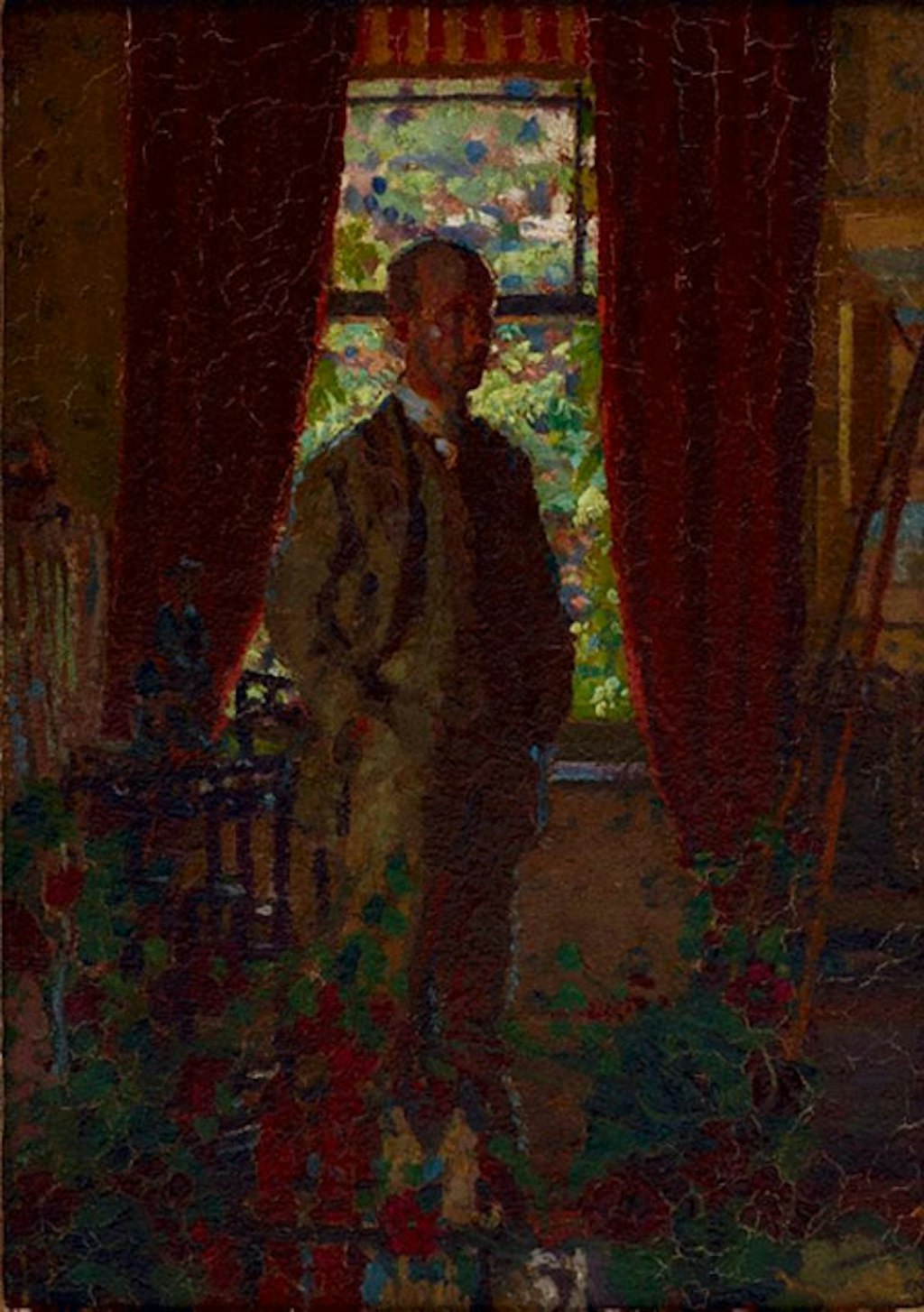

Harold Gilman Self-portrait c1908-09, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Harold Gilman Self-portrait c1908-09, Art Gallery of New South Wales

In the UK, the post-impressionist painter Harold Gilman contracted the illness after nursing his artist friend Charles Ginner. The flu then developed into pneumonia for both of them and Gilman died in October 1919. The Gallery has a self-portrait of Gilman that shows the Camden Town Group founder in a dark interior, haloed by a luminous garden seen through a window behind him. Ginner later described Gilman’s death as ‘a great loss to the modern art movements in this country’, remembering him as ‘a man of untiring energy in the furtherance of true and sincere art’.

It’s not all doom and gloom, however. Most of those who contracted the Spanish flu managed to recover, including Gilman’s colleague Christopher Nevinson, the Australian symbolist artist Sydney Long and the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch.

Munch was one of the few artists to depict himself suffering from Spanish flu, which he followed up with a portrait of himself in recovery. After a childhood overshadowed by illness and bereavement, Munch was fascinated by mortality, which is exemplified by his 1896 etching The sick child in the Gallery’s collection.

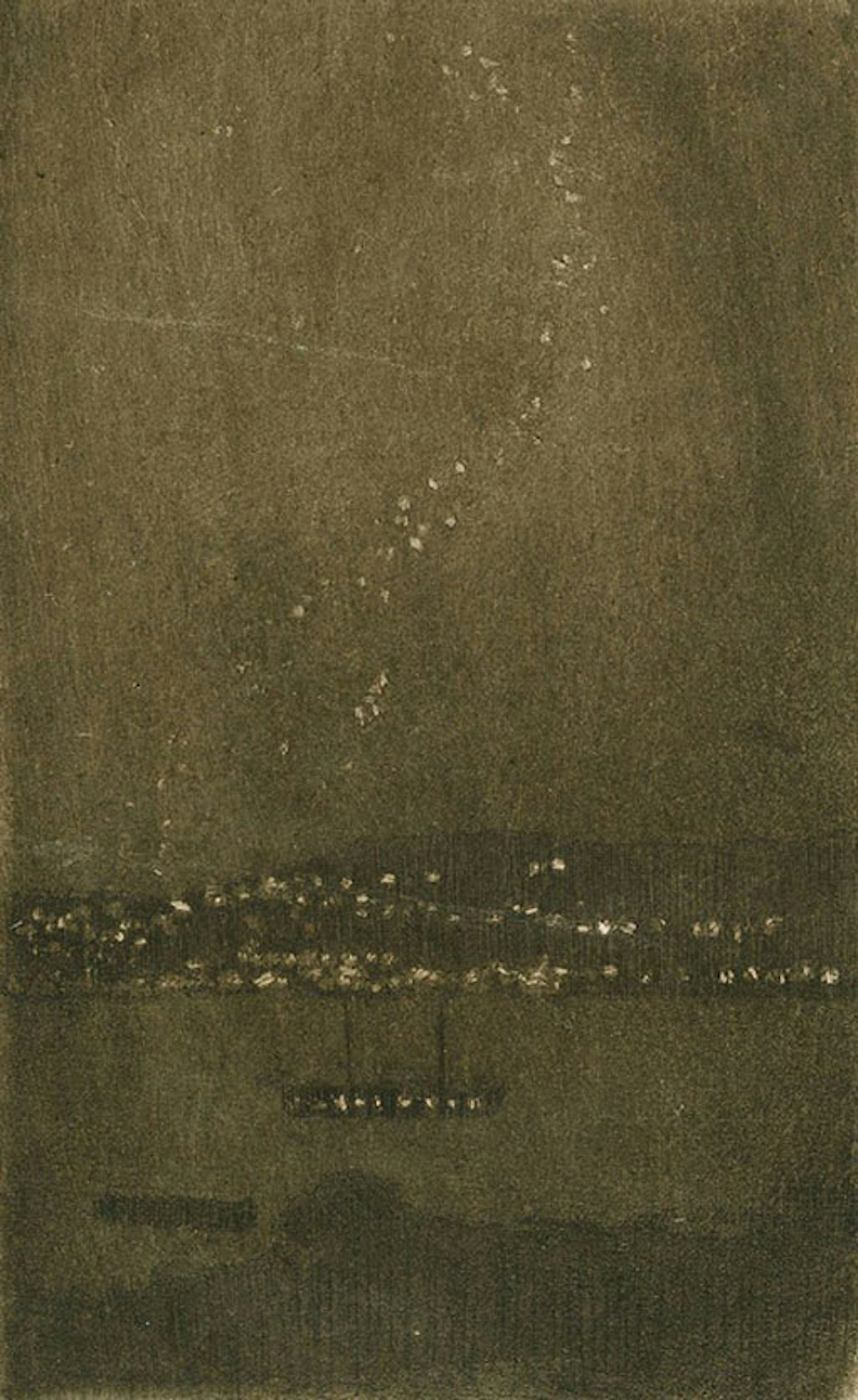

Jessie Traill Stars of heaven and earth, Sydney Harbour 1920, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Estate of the artist. Licensed by Copyright Agency

Jessie Traill Stars of heaven and earth, Sydney Harbour 1920, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Estate of the artist. Licensed by Copyright Agency

Finally, there were those who nursed the ill back to health. Australian artist Jessie Traill was one of the many brave women who volunteered to work in military base hospitals during the First World War. She was stationed near Rouen, France, between 1915 and 1919 to care for the wounded and those affected by the influenza pandemic. She returned to Australia in 1920, where she resumed a successful career as an artist. Traill’s etching Stars of heaven and earth, Sydney Harbour was completed shortly after her return home. This tranquil scene seems to put humanity’s dramas into perspective against the vast glittering firmament. And, for me, it firmly links the past with the present by depicting the harbour I live and work by.

These artworks serve to remind us that beyond unfathomable statistics there are individuals with rich lives and stories to tell. While we may face loss and hardship, we also encounter compassion and resilience.

We live in very different times to the people confronted by the influenza pandemic of 1918–19. Medical and technological advancements, vastly improved communications and understanding of basic hygiene all aid our chances of overcoming the present crisis. We don’t yet know what life will be like after we emerge from isolation, but I am eager to see how artists will respond to these troubled times. And I wonder what people will glean from their art 100 years from today.

![Edvard Munch [w:473.1987[The sick child]] 1896, Art Gallery of New South Wales](https://www.datocms-assets.com/42890/1632958788-473-1987-mm.jpg?fit=clip&iptc=allow&w=1024)

Edvard Munch The sick child 1896, Art Gallery of New South Wales