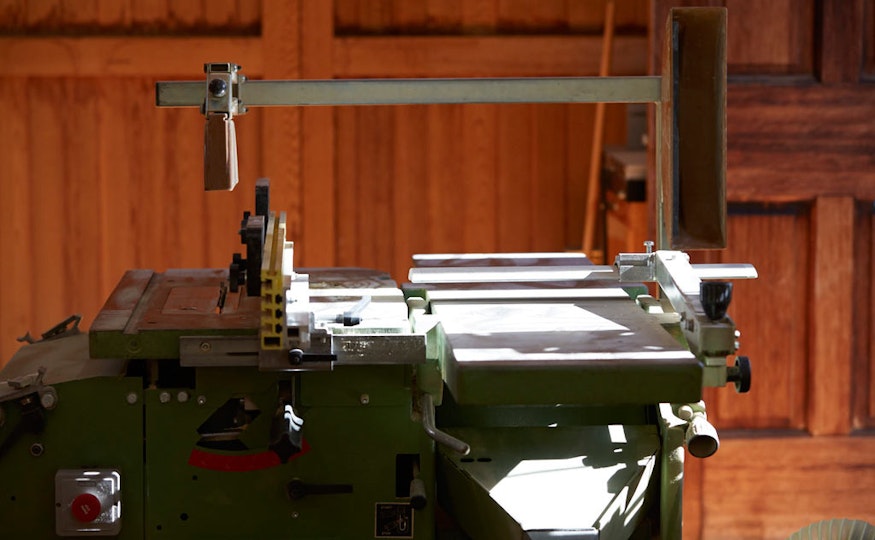

Inside a framing studio

David Butler and Tom Langlands in David’s studio with the frame they made for Julian Ashton’s 1889 painting The prospector

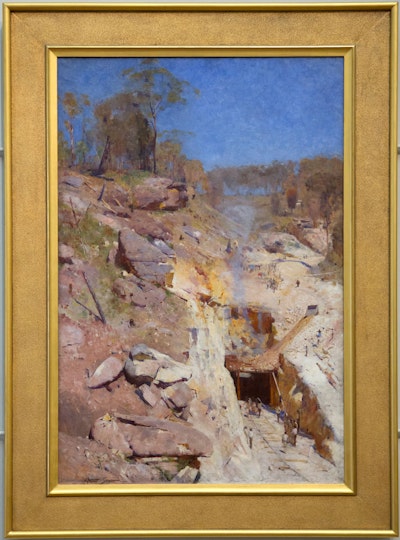

Inside his Blue Mountains studio, the Art Gallery of NSW’s retiring frame-maker, David Butler, and his apprentice of four years, assistant conservator Tom Langlands, have been gilding a new frame for Julian Ashton’s heroic painting The prospector 1889.

The frame is far from the largest David has made in the 30 years he has worked at the Gallery, still, it seems vast lying on its side. At 260 × 170 × 140 centimetres, the frame has a relatively simple design, he says, which is based on a c1889–1902 photograph from the Gallery’s archive of the work in its original frame. It has a twin in another frame David and Tom made for François Sallé’s The anatomy class at the École des beaux-arts 1888.

Frames have seldom been paid much attention in art history. By their nature, they are fated to be outshone, to live constantly in the margins. But the right frame on a painting is a munificent object. A frame stresses the scale and physicality of a work. Its three dimensions illuminate dimension in the picture itself; in a social media-obsessed culture, it anchors a painting to the real world. It both marks the end of the picture and raises questions of what’s beyond. At the same time, frames are art’s great scene-setters – like a stage curtain and arc, a frame directs the gaze.

‘A frame encloses a painting,’ says Tom, ‘whereas some artists don’t want their works to be enclosed.’ ‘But there’s a whole other side to it as well,’ says David, ‘because frames reflect the tastes of the period. This might cause an aesthetic conundrum, but I think it’s really important that works of art are seen as they were intended to be seen. When you are replicating an original frame, the objective is to achieve this historical context. How the frame looks to a contemporary viewer is not necessarily relevant.’

This idea has only recently become popular in art museums. Historically, when masterpieces have passed into the hands of a new owner, too often their frames have been cast aside. As a result, original frames have rarely remained with their paintings.

‘In the mid 20th century, galleries around the world, but particularly in Australia, were removing original frames from paintings and replacing them with profiles of the day,’ says David. ‘They were removed and sold off at auctions or they just disappeared. The Gallery lost a huge number of original frames at this time. Much of the work I’ve been doing over the last 30 years is replacing – or replicating – what was lost.’

In an age of mass production and 3D printing, visiting David’s studio is to step back in time. He is largely self-taught in this work that combines the skills of a carpenter and a sculptor. There is the sense that the tools and materials found here are more or less the same ones frame-makers have used for centuries.

‘A lot of 19th-century frames are fairly ornate,’ says David. ‘The ornaments are usually moulded from composition material made from a mixture of gilders whiting, hide glue, rabbit skin glue, rosin – that is, resin extracted from pine trees – and linseed oil. Glycerol is often added to modern formulations to stabilise the mixture and reduce the tendency to crack during drying.’

‘That makes a material that’s putty-like when it’s warm, which means it can be applied to complex moulding profiles, but as it cools it becomes more solid and it is virtually rockhard when it dries out. There is really no synthetic substitute.’

Before any of this occurs, David’s frames begin with a search for old photographs or drawings of the work’s original frame, or, failing that, one for a similar work by the artist. The Gallery’s own archive is often the first point of call before the search extends to other galleries.

‘The Gallery’s Briton Riviere painting Requiescat 1888 is an example of a painting that we had no reference material for the frame,’ he says, ‘but the Tate, who had many examples of original frames for Riviere paintings, sent me a number of images and I was able to make a faithful replica.’

Archive photo from c1889–1902 showing The prospector in its original frame, just to the left of the central sculpture

Much like the frames themselves, David’s impact on the walls of galleries across the country is barely perceived by those who visit for the paintings. You won’t find his name on any wall label, but walk through the Gallery’s Grand Courts and his frames are in every room – the monumental frame bordering Edouard Detaille’s Vive L’Empereur! 1891 is his work, so too the opulently detailed edging to James Tissot’s The widower 1876, and the elaborate, hand-carved – and, for that reason, David’s favourite – frame that holds George Lambert’s Holiday in Essex 1910.

David first came to Australia from England in 1976, where he applied for two jobs – one at a carwash, the other at a picture framer’s, which, fortunately, was the one he got. Eleven years, various other jobs in the field, and a few extended overseas trips later, he took a casual part time job as assistant frames conservator at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. He worked alongside the Gallery’s very first frames conservator – these days, head of frame conservation – Margaret Sawicki. When a third frames conservator, Barbara Dabrowa, started in 1995, David stopped commuting in order to make new frames from the studio that he built alongside his Mountains home.

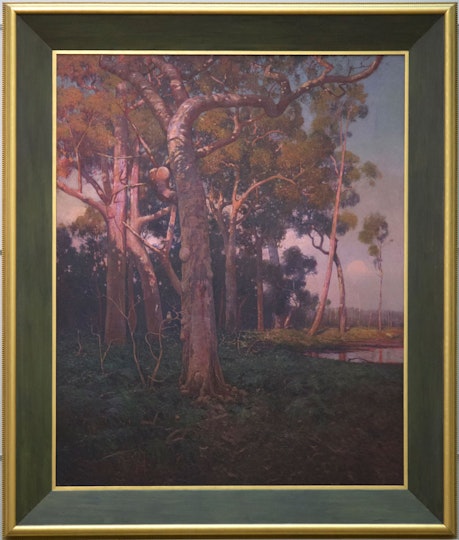

Two days a week for the past four years, thanks to support from the Clitheroe Foundation and the Nelson Meers Foundation, David has been training Tom to take over. They have made new frames for paintings including Arthur Streeton’s Fire’s on 1891, Tom Roberts’ Jealousy 1889 and W Lister Lister’s The golden splendour of the bush c1906.

During this time, the Conservation Department was also preparing for the exhibition Victorian watercolours. While his colleagues worked on restoring artworks and existing original frames, Tom made nine new frames. Two of these – those for William Henry Hunt’s The cow shed c1835–40 and George Price Boyce’s An old farmhouse at Hambledon, Surrey c1876 – were standouts for Tom. ‘They are Rossetti-style Pre-Raphaelite frames,’ he says. ‘They were made of oak and required a bit of carving and I really enjoyed making them.’

In this image gallery, you can see all these works in their frames and also take a glimpse inside David’s framing studio with a selection of photographs from a visit with Gallery photographer Felicity Jenkins.

David in another part of his studio. In the background are mouldings that he has pre-cut; on the left is the slip for The prospector.

Edouard Detaille’s Vive L’Empereur! 1891

François Sallé’s The anatomy class at the École des beaux-arts 1888

Briton Riviere’s Requiescat 1888

James Tissot’s The widower 1876.

George Lambert’s Holiday in Essex 1910

Arthur Streeton’s Fire’s on 1891

Tom Roberts’ Jealousy 1889

W Lister Lister’s The golden splendour of the bush c1906

William Henry Hunt’s The cow shed c1835–40

George Price Boyce’s An old farmhouse at Hambledon, Surrey c1876

A version of this article first appeared in Look – the Gallery’s members magazine

Read Tom Langlands’ blog post from a year into his training