A light in dark times

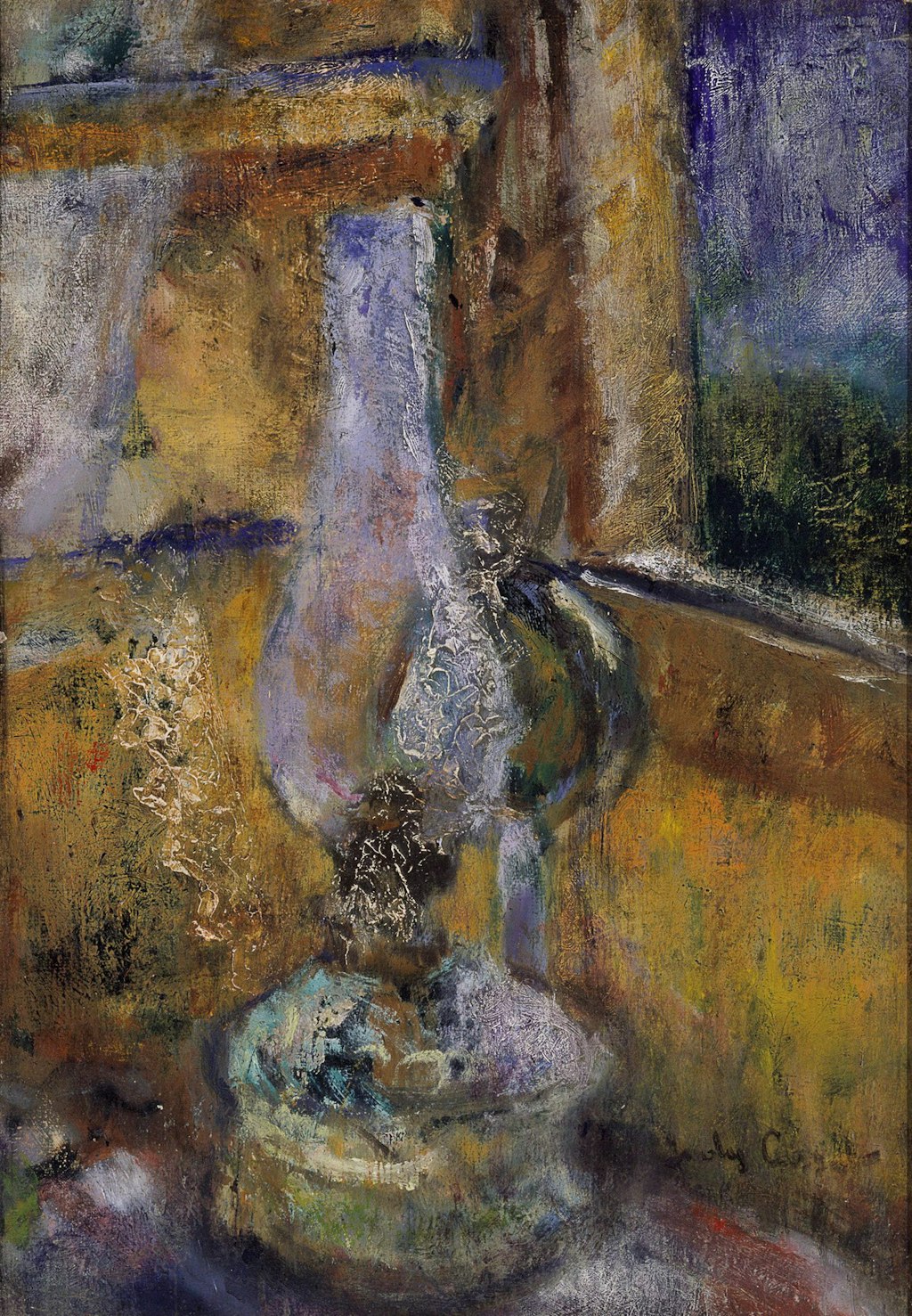

Judy Cassab Kerosene lamp, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Judy Cassab

Judy Cassab Kerosene lamp, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Judy Cassab

The month of April is a significant one for people of faith, with major religious celebrations falling during this time. The festival of Passover (Pesach) – which, in 2020, is celebrated from 8 to 16 April – commemorates the liberation of the Jewish people from enslavement in Egypt. Families gather for a ritual meal called the Seder, where the Biblical story is retold, wine is drunk and symbolic foods are shared. It is customary to invite guests, but this year the Seder has been held in isolation, without guests and with families often separated from their loved ones.

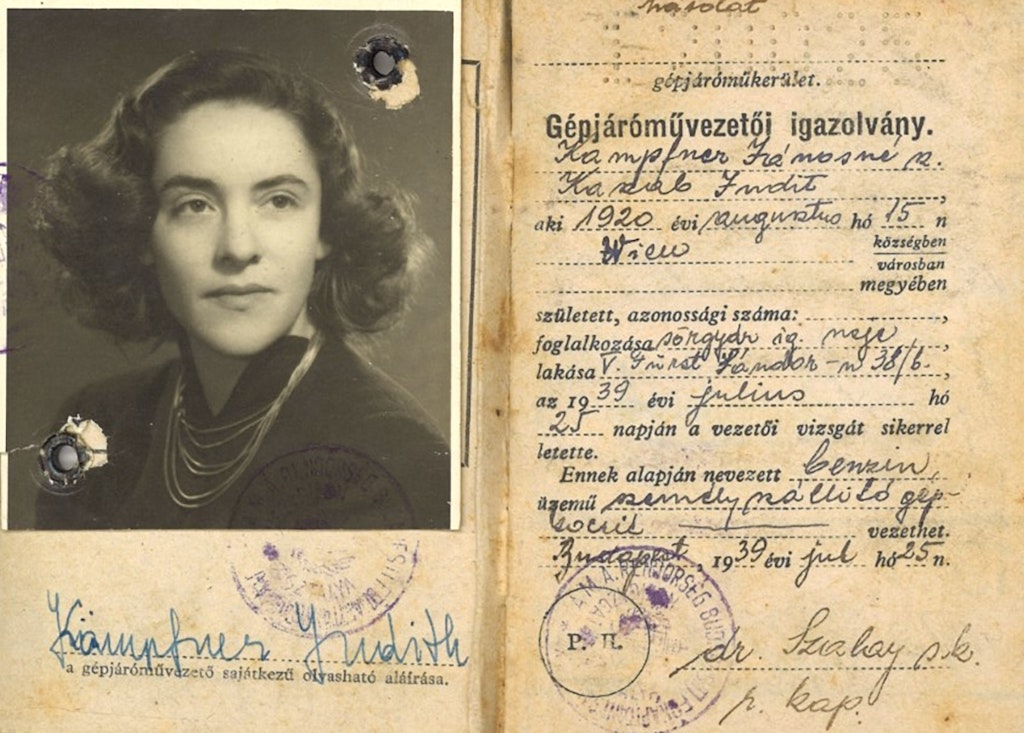

Many Australian Jews have personal stories of enslavement and exodus. Artist Judy Cassab, who died in Sydney in 2015, was one of these people. Her archive, which was recently donated to the National Art Archive at the Art Gallery of NSW, contains records documenting her birth in Vienna in 1920, art studies in Prague, the years during World War II when she lived under a false identity while her husband was in a Nazi labour camp, and then the devastating return to the family home in the hope of finding her mother and grandmother, only to discover that they had not survived the Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp.

Judy Cassab’s passport, National Art Archive, Art Gallery of New South Wales

There is also a diary with a photograph taken in 1932 pasted onto the inside cover. It is a group portrait of her piano school, of boys and girls aged between five and 13, all beaming with life and promise. Cassab has marked some students with numbers and annotated: ‘4. Agi Iszak … was deported to Auschwitz, pregnant. The baby was killed … 5. Magda Kaliman was killed in Auschwitz. 7. Eva Feher. I picked her up every morning on our way to high school. She was killed in deportation camp. 8. Is me’. I was deeply moved when I stumbled upon the photograph and wondered how anyone could survive such loss. But many did, including Cassab. For her, art was a great life-affirming act in the midst of senseless destruction.

Judy Cassab (at the left of the back row, in black) with fellow students in a 1932 photograph from one of her diaries, National Art Archive, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Best known for her portraits, Cassab was the first woman to win the Archibald twice. She was awarded the prize in 1960 and in 1967 and both works are now in the Gallery’s collection. The Gallery is also fortunate to have one of her works from 1950, painted in Vienna, when she was in exodus with her young family: displaced persons waiting to find asylum somewhere. Kerosene lamp was included in her first Australian exhibition. One critic glibly remarked that ‘Aladdin’s lamp’ would be a better title for it. But surely this mysterious painting is more than a fantasy image of a wish-fulfilling lamp? The barely discernible face in the background is the artist’s. Light has an important symbolic role in Judaism. It ushers in the Sabbath and candles are lit at festivals, including during Passover. Women traditionally perform this ritual. For me, the tiny flicker of Cassab’s lamp suggests the fragility of life. It also kindles hope; painted by an artist who had lived through dark times and who had learned that these too would pass.