The rose and the thistle

It sounds like the name of an English pub, doesn’t it? But I’m talking about the two plants that inspired the creation of a fabulous floral display in our exhibition The lost prince and the winter queen: royal portraits from the National Portrait Gallery, London.

It’s not often that exhibitions call for floral decoration (after all, the artworks on display dazzle the eye enough). But the arrival of royalty at the Gallery seemed to call for a ceremonial flourish – especially as these personages are over 400 years old. So, what kind of flowers would be worthy of one of England’s most beloved princes, Henry, Prince of Wales, and his legendary sister, Princess Elizabeth, who later became the Queen of Bohemia?

Left to right: Robert Peake the Elder Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia c1610 and Prince of Wales c1610, National Portrait Gallery, London

I first looked to the paintings of the era for ideas, seeking out clues as to what kind of flowers the Stuart royals may have favoured. Few 16th- or early 17th-century paintings depict fresh flowers in abundance, even though gardens surrounded royal palaces and flower motifs were common in clothing, furniture and other designed objects. There are, however, a couple of botanical references in the two portraits exhibited in our show: Elizabeth’s costume is embroidered with tiny rosebuds, while the view through Henry’s window reveals a garden, probably the grounds of Richmond Palace, where the young prince had engaged French garden designers and engineers to lay out new water features and follies.

More commonly, flowers in Elizabethan and Jacobean portraits tend to appear as a single stem or two, either tucked into a bodice or held in the hand.

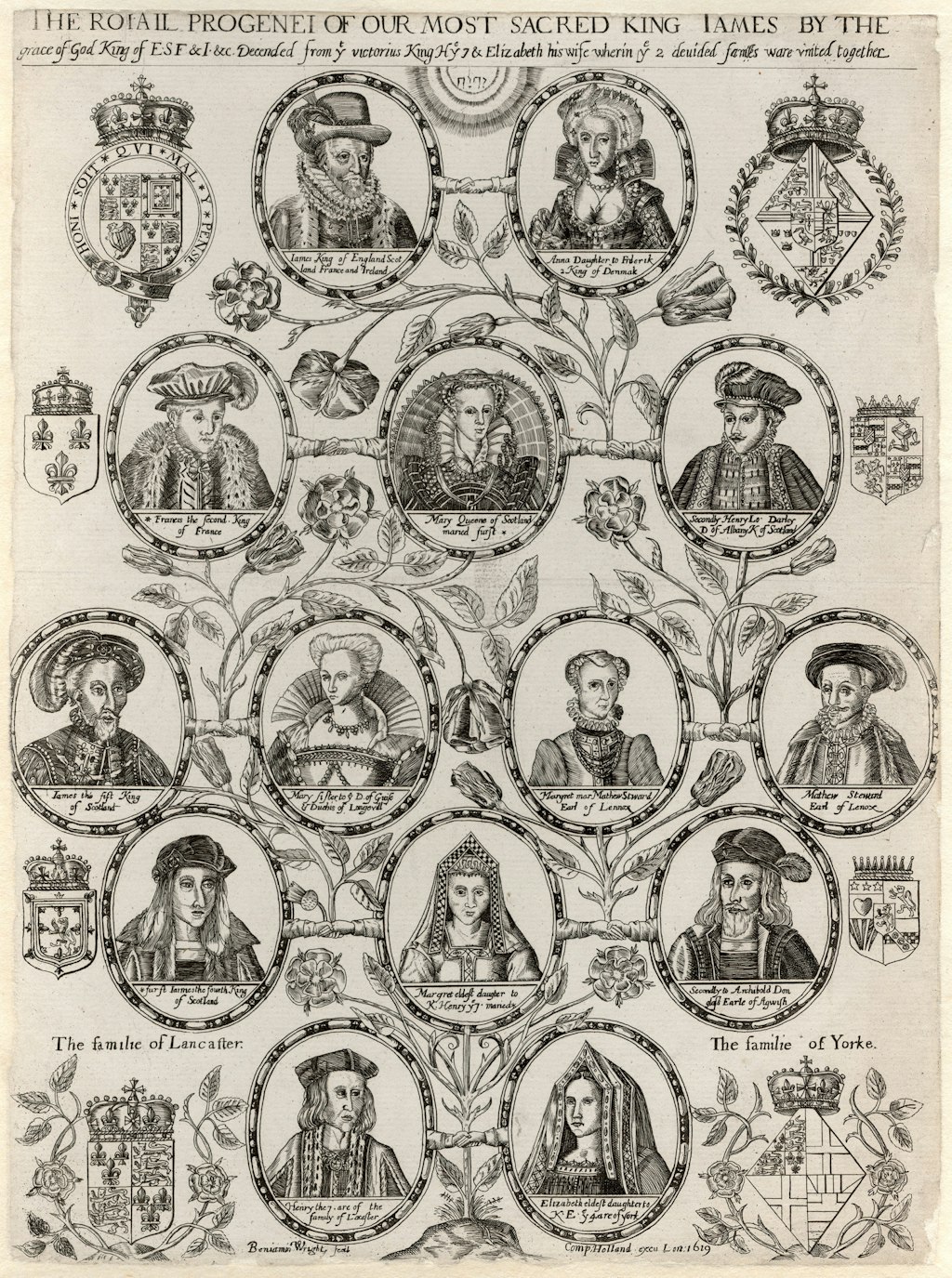

The most common species is, of course, the rose — the symbol of the Tudor family, who had ruled England from 1485 to 1603. Henry and Elizabeth’s father James I was not a Tudor (he was a Stuart) but he was distantly related and he liked to emphasise it – the Tudor rose appears in several of his portraits. When he became King of England in 1603, several family trees were printed, tracing his ancestry back to Henry VII — the first Tudor king — on both sides of the family. As if to drive the point home, the trees are always intertwined with rambling, leafy roses. The flower eventually became synonymous with England itself.

Benjamin Wright (after an unknown artist) The Roiail Progenei of our Most Sacred King James, line engraving, 1619–15, National Portrait Gallery London

If the rose represents England, the thistle is the plant of Scotland – King James’ other, original dominion. A lovely poem, invoking the union of Scotland and England that occurred under King James, appears in the emblem book Minerva Britanna, written by Henry Peacham in 1612 and dedicated to Henry, Prince of Wales. Peacham begins by making a virtue of the thistle’s prickliness, then brings in the love-association of the rose (Cythera being the mythical island of love):

The Thistle, arm’d with vengeaunce for his foe,

And here the Rose, faire Cythera’s flower;

Together in perpetuall league doe growe,

On whome the Heavens doe all their favours power…

The rose and thistle appeared everywhere in my research. Another book by Peacham, published in 1613, combines mourning poetry for Henry and celebratory accounts of Elizabeth’s marriage (his funeral and her wedding occurred within months of each other). It contains a suite of royal insignia that includes Rosa Britannica and Carduus Scotius. A suit of armour owned by the prince is resplendent with gold designs of the two plants (along with fleur de lys, the floral emblem of France, to which the English still had a claim).

So the rose and thistle clearly had to be the blooms for Henry and Elizabeth. Enter Saskia Havekes and her team from Grandiflora in Sydney’s Potts Point, who’ve created a mass of lush green with flickers of red and white, mimicking the intricate patterning of Jacobean painting; garlands of magnolia foliage to lend a sense of regal ceremony; and trailing ivy and rising bare branches in a wistful evocation of the exhibition’s romantic title. It’s like a wild English woodland in miniature, but with a nod to the clipped symmetry of the Renaissance garden. I love it!