Sun, sand and social responsibility

Charles Meere Australian beach pattern 1940, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Estate of Charles Meere / Copyright Agency

We view the art of the past through the lens of our present. Today, as the threat of COVID-19 locks down our beaches, one of the most recognised paintings in the Art Gallery of NSW collection has taken on urgent new meanings which add to the perplexing ones of its past.

The English-born Charles Meere started working on Australian beach pattern in his Sydney studio in 1939. It remains something of an enigma, posing some puzzling propositions, which have been debated and reconsidered over time.

![Charles Meere [w:330.1979[Cartoon for ‘Australian beach pattern’]] 1939, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Charles Meere Estate. Licensed by Copyright Agency](https://www.datocms-assets.com/42890/1632974088-330-1979-mm.jpg?fit=clip&iptc=allow&w=1024)

Charles Meere Cartoon for ‘Australian beach pattern’ 1939, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Charles Meere Estate. Licensed by Copyright Agency

Painted at a time when the image of the Anglo, bronzed male lifesaver had become a ‘national type’, it makes us ask: was Meere celebrating or satirising the notion of a physically perfected beach-dwelling race? As Australian society emerged from the devastation of World War I, endured economic depression and headed toward another world conflict, was Meere painting a fortified race, the brave new bodies of the modern world? Or do their hyper-real qualities tell of the absurdity of such an idea?

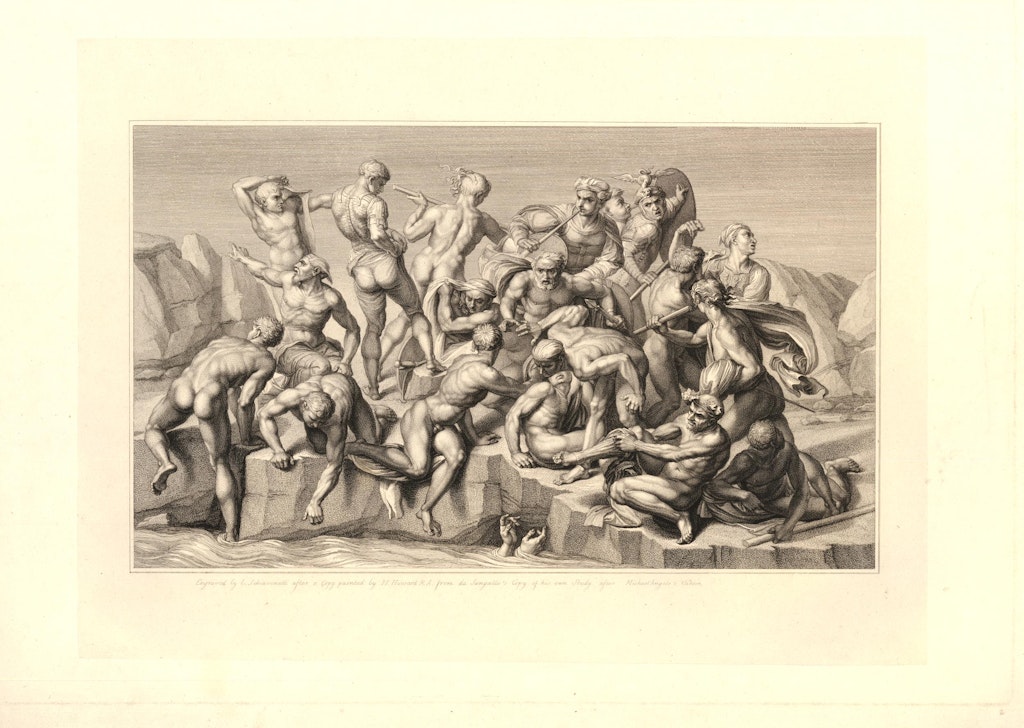

Australian beach pattern is often compared to paintings of Renaissance battle scenes. including Michelangelo’s Battle of Anghiari, a now-destroyed fresco known to us from the drawing by Artistotle da Sangallo known as Battle of Cascina 1542, and Paolo Uccello’s The battle of San Romano.

Like these paintings, Meere’s work is instilled with a mighty sense of suspended energy. The figures and the atmosphere around them are dense with strength. The beach, as Meere would have it, is hard work, not so much a site of leisure but an exhaustive spectacle of enhanced physicality.

A print made by Luigi Schiavonetti of Artistotle da Sangallo’s Battle of Cascina, after Michelangelo, in the British Museum. Photo © Trustees of the British Museum, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license

This brings us to what is disturbing and fascinating about the painting. It presents figures whose inner impulses seem to have been negated – humans void of their humanity. Artist and critic James Gleeson once noted of this work that ‘some essential quality has been missed and that quality is warmth’. But the most enduring summation of this painting surely comes from the Gallery’s former head of public programs, Linda Slutzkin, who referred to it as ‘Spartans in Speedos’. Meere’s figures have all the buff of warriors, but with nowhere really to go.

Australian beach pattern has often been referred to by artists critiquing notions of such national ‘types’, most famously when Anne Zahalka repopulated Meere’s beach tableau with a diverse group of ordinary-looking folk in The bathers 1989. Zahalka’s work formed part of a series, Bondi: playground of the Pacific, in which she challenged the artifice of national identity and the mythologised place of the beach within it.

![Anne Zahalka [w:96.1990[The bathers]] 1989, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Anne Zahalka. Licensed by Copyright Agency](https://www.datocms-assets.com/42890/1632973592-96-1990-mm.jpg?fit=clip&iptc=allow&w=1024)

Anne Zahalka The bathers 1989, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Anne Zahalka. Licensed by Copyright Agency

But if, in its day, the proposal of Meere’s racially fixed, eugenically ‘cleansed’ bodies seemed frighteningly real (the unfathomable horror of Europe’s totalitarian regimes had started to play out), his beach scene is now menacing to us in a whole new way.

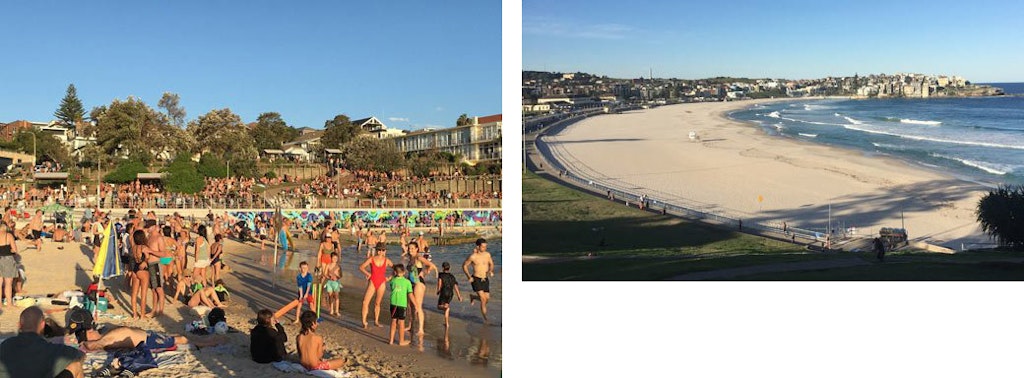

In this anxious time of social distancing, the physical closeness of Meere’s painted bodies appears sinister, and the work calls to mind the shocking images of the crowds that made their way to Bondi and other beaches before closures were enforced. The beach fashion today may be a little more slim-lined, the bodies often tattooed, but otherwise Meere’s painting is uncannily close to those Sydney scenes of recent times.

Left to right: Crowds at Bondi Beach on 20 March 2020, and an empty beach after authorities closed it down as part of restrictions to stop the spread of COVID-19

There is a funny side to the prescient parallels of Meere’s ‘Spartans in Speedos’ with those bizarre beach crowds. But there’s a cutting one as well. While those on the medical front-line anxiously waited for the full onslaught of the COVID-19 virus, there were claims from outraged members of beach-going communities of their right to carry on with their lifestyles. Does this imply a lingering sense of Meere’s inflated and absurd image of a supposed national type in present-day consciousness? Of a worldview in which physicality born of beach and sun takes precedence over social concern?

In her 2017 book Discovering Charles Meere, Joy Eadie suggests Australian beach pattern was Meere’s comment on an unthinking society being led toward the catastrophe of another world war. As we currently confront a shared disaster, the painting might serve as a reminder of what can be lost if we lose sight of our sense of a socialised humanity.