Time alone with art

I don’t know about you, but the temporal markers upon which I ordinarily rely – minutes and hours, weekdays and weekends – have now completely dissolved. Today, tomorrow and yesterday. Monday, Tuesday and Saturday. Morning and evening. Life is no longer segmented, organised, comprehended and ritualised according to these structures.

At the beginning of our new not-so-normal (I am holding on to this marker of time, because if there was a beginning then there must be an end), I clung to these structures. Faced with two weeks of quarantine, and an indeterminate stretch of time working from home, I started each day by scheduling the hours lying languorously ahead of me into neat and comprehensible intervals. (6.30–7.30am: drink coffee and read news. Yes, I can do that. Look at me go, next task please!)

A schedule gave me order when everything felt disorderly and disorientating. It allowed me to not only count the days but to give value to the act of getting through them. It reminded me to indeed take things day by day.

This early period is what I refer to as my ‘On Kawara phase’. A reclusive but nonetheless seminal figure of conceptual art, On Kawara painted the date on the centre of a canvas each day for almost 50 years, from 1965 until 2014, as part of his Today series. In the Gallery’s collection, we have another of his time-based projects, One million years 1999. These two artist books each list, in a regimented serial format, a million years. One book reaches back through time, while the other extends into the future.

![On Kawara [w[One million years]] 1999, Art Gallery of New South Wales © The Estate of On Kawara](https://www.datocms-assets.com/42890/1632962565-235-2016ab-view03.jpg?fit=clip&iptc=allow&w=1024)

On Kawara One million years 1999, Art Gallery of New South Wales © The Estate of On Kawara

My ‘On Kawara phase’ was punctuated by ‘Micah Lexier moments’. The scrawled abstract imagery of Lexier’s steel wall-work A minute of my time (July 12, 2000 14:42–14:43) is based upon a drawing that took the artist exactly one minute to create. (Why mark the days, when you can mark the minutes!) This recent addition to the Gallery’s collection sees a small, fleeting moment given weight, scale and permanence.

![The drawing Micah Lexier used for his work [w:8.2019[A minute of my time (July 12, 2000 14:42–14:43)]] 2000, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Micah Lexier](https://www.datocms-assets.com/42890/1632962072-micahlexier.jpg?fit=clip&iptc=allow&w=1024)

The drawing Micah Lexier used for his work A minute of my time (July 12, 2000 14:42–14:43) 2000, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Micah Lexier

But as quickly as my zeal for schedules and records came, it dissipated, and I found myself sliding towards a ‘Spencer Finch state of being’. Time became manifest through slow and slight changes in light. The way it spread across or retreated from my apartment. The way it gradually brought one detail into view before rolling effortlessly on to another – a sequence captured by Finch, with remarkable sensitivity, in his photographs 56 minutes (after Kawabata) Spring 2004.

![Spencer Finch [w[56 minutes (after Kawabata) Spring]] 2004, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Spencer Finch](https://www.datocms-assets.com/42890/1632963350-145-2014a-1.jpg?fit=clip&iptc=allow&w=1024)

Spencer Finch 56 minutes (after Kawabata) Spring 2004, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Spencer Finch

By this point, discrete measurements of time became edgeless, merging to form a perpetual present tense. Its activities and rhythms, once rapid and frenetic, quietened and steadied. My ‘Daniel Crooks moment’ had arrived. Everyday motions became stretched and viscous like the red kite in his work Static no. 13 (Underwater flight recording) 2010. They could be trailed like a gymnast’s ribbon. Or mapped like the pulse on a heart rate monitor.

![Daniel Crooks [w[Static no. 13 (Underwater flight recording)]] 2010, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Daniel Crooks](https://www.datocms-assets.com/42890/1632961460-519-2017-still01-mm.jpg?fit=clip&iptc=allow&w=1024)

Daniel Crooks Static no. 13 (Underwater flight recording) 2010, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Daniel Crooks

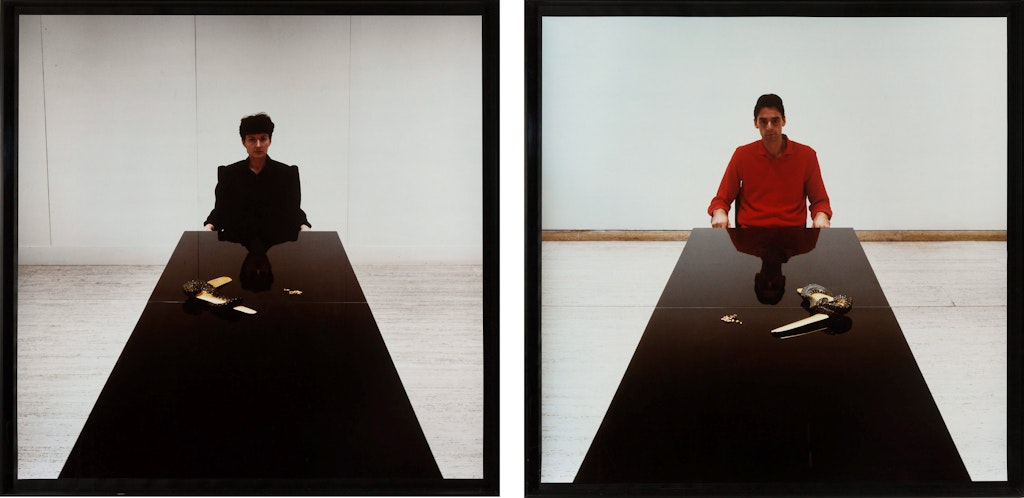

But soon poetics turned into endurance as I entered my ‘Marina Abramovic and Ulay phase’. This was largely characterised by an unwavering commitment to staring at the wall. My perseverance, however, didn’t match the staying power that the duo demonstrated in their 1981 performance at the Gallery, which lasted an impressive 16 days. Yet the meditative state was hard to shake.

Marina Abramovic and Ulay Gold found by the artists 1981 from the series Nightsea crossing 1981-86, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Marina Abramovic & Ulay, 1981/Bild-Kunst. Licensed by Copyright Agency. Photos: John Lethbridge

And so now, here I am, in a place where time no longer holds any of its previous import. (The black hole!) I’ve moved from the conceptual rigor of 1960s artistic practice, passed by 1980s performance, and ended up in the realm of the non-representational. Abstraction has long investigated new dimensions of space and time within the medium of painting; the ‘Dale Frank cosmos’ feels like a fitting final stage.

I find myself roaming monochromes, just a tiny speck in a very large, interconnected universe, and thinking about how, although distance defines our lives right now, the invisible threads binding us are felt anew.

![Dale Frank [w[Stephen Hawking and the illusion of size]] 2001, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Dale Frank](https://www.datocms-assets.com/42890/1632960820-404-2001-mm.jpg?fit=clip&iptc=allow&w=1024)

Dale Frank Stephen Hawking and the illusion of size 2001, Art Gallery of New South Wales © Dale Frank