Webber work reveals its secrets

John Webber’s A view of Otaheite Peha after conservation

For many years, we’ve been unable to exhibit the Art Gallery of NSW’s only painting by an artist of Captain James Cook’s last voyage to the Pacific due to the poor condition of both the painting and frame. A recent conservation project, funded by the Conservation Benefactors, has not only returned the work to display, but also revealed some secrets.

British painter John Webber (1751–1793) was official artist on Cook’s third and final voyage to the Pacific on the Resolution from 1776. Returning to London in 1780, after Cook’s death in Hawaii, Webber began a series of works based on the voyage, including A view of Otaheite Peha, a Tahitian landscape that the Art Gallery of NSW bought in 1976.

Over time, the painting’s varnish had darkened and yellowed and a previous restorer’s mismatched paint strokes in the central mountain had become obvious. In addition, the gold finish on the carved frame had been repainted and was now a dark bronze colour.

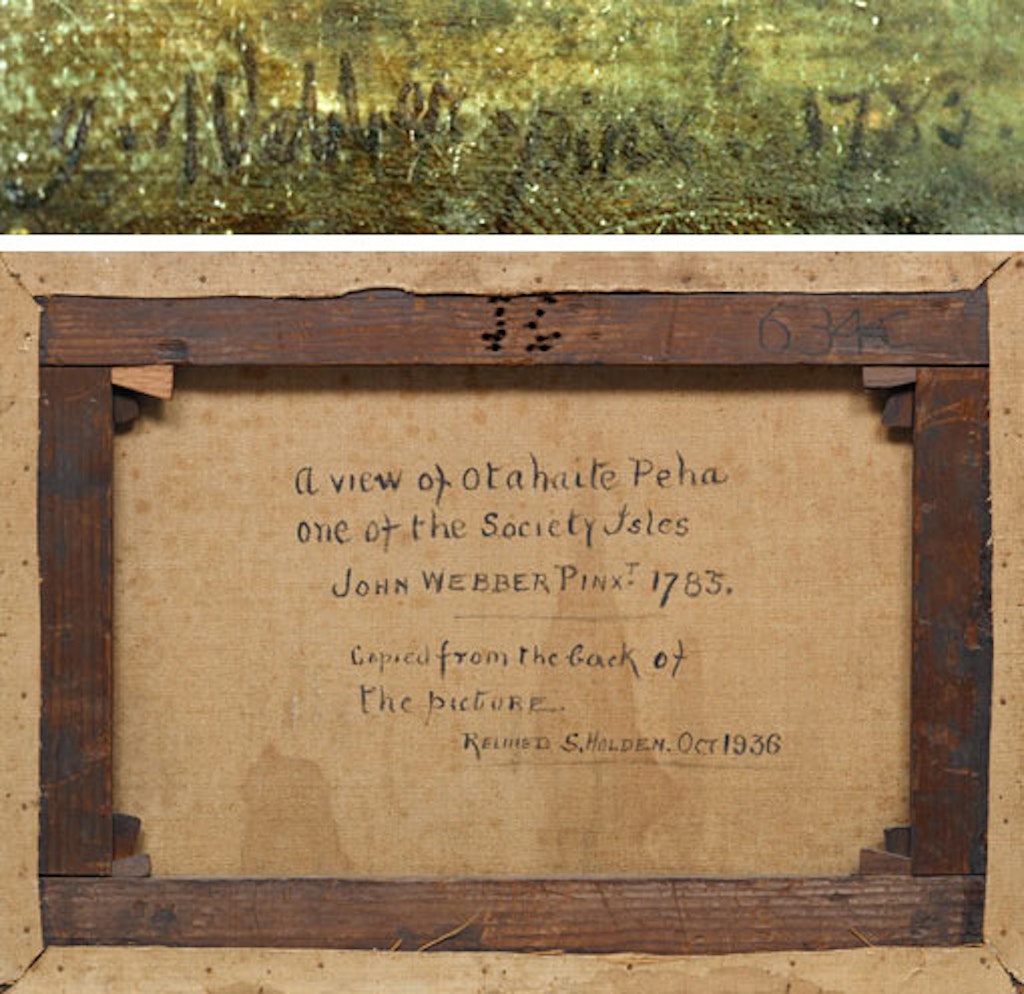

There was also some question that the signature and date on the painting at the lower left corner might have been added by a restorer and may not be the artist’s. An inscription on the back of the painting, which could potentially confirm the date, was obscured by a lining. Lining is a conservation treatment commonly undertaken in the past to strengthen the painting canvas by adhering a new canvas to the back. A restorer had helpfully noted on the lining canvas that there was an inscription present on the original canvas.

Our conservation treatment began with the removal of the lining canvas to reveal the inscription. The painting was temporarily protected with a layer of tissue paper adhered with starch paste to the face of the work. The lining canvas was removed by carefully peeling it away from the back of the painting.

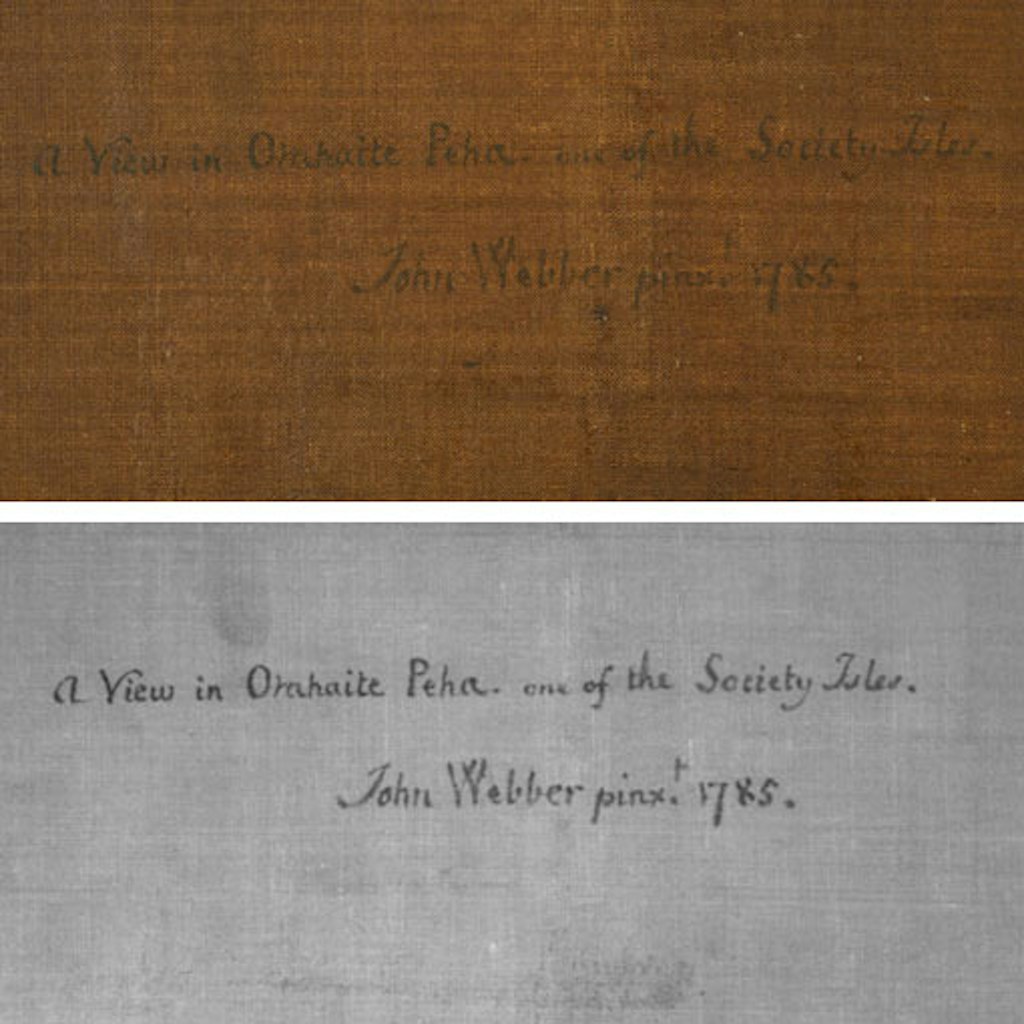

An inscription was revealed but not easily read until all the old lining glue was removed.

An infrared photograph shows the inscription clearer than can be seen by the naked eye. Now we see for the first time since the painting was lined in 1936, John Webber’s own signature, title and his date for the painting … 1785. Two years later than the date on the front of the painting.

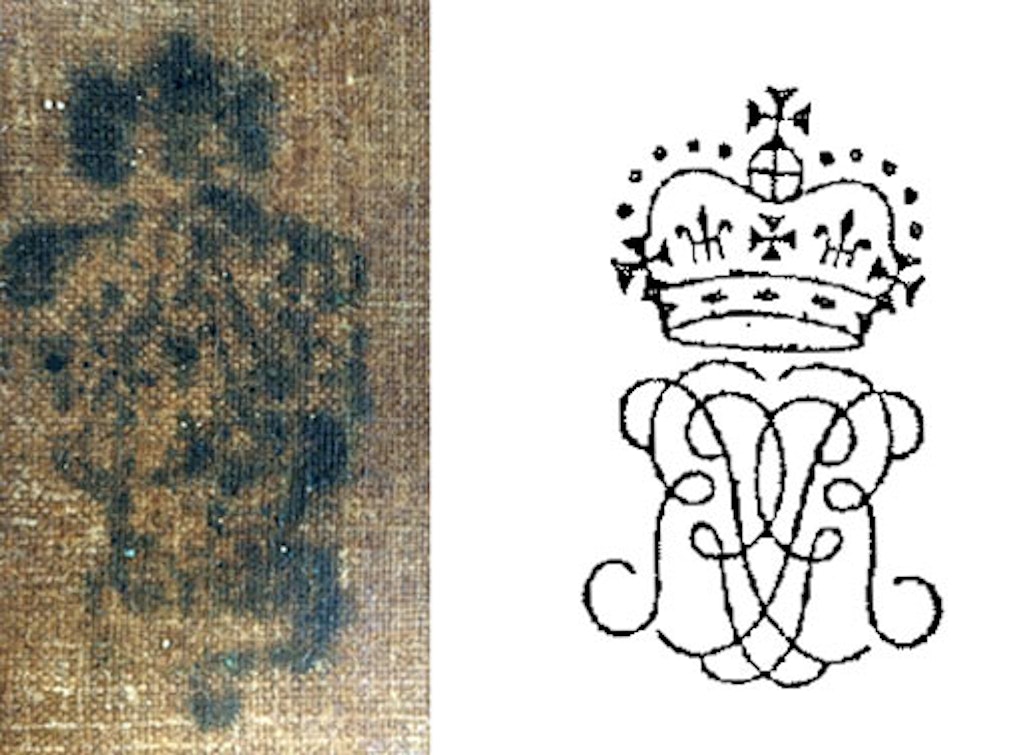

Another mark was revealed by the removal of the lining canvas. An ink stamp at the edge of the canvas is difficult to decipher but is probably a customs stamp consisting of a royal crown and a double reversed King George III, (George Rex) GR, monogram. These stamps were used from 1774 for the purpose of recording payment of duty on foreign-made linens when they arrived in England.

In the next steps in our conservation process, the painting was reattached to its stretcher and the tissue paper removed from the face. The process of dissolving the darkened varnish layers commenced, slowly revealing the bright blue sky and green vegetation as they were painted by the artist. The signature was found by microscopic study to have been added over varnish layers and cracks in the paint and was also removed. An original signature was found below but the date had been obscured by the artist with a later paint stroke.

There were further surprises in store when Margaret Sawicki, head of frames conservation, and Emma Rouse began work on the frame. When the brass-based paint layer was removed, a dark green layer was revealed below the paint. This was a copper corrosion product formed by the reaction of the copper-containing metallic flakes in the paint-and-oil medium. Slowly this too was removed, revealing burnished gold leaf preserved on the uppermost ornaments at the corners and in the centres; everywhere else, the gold leaf had all but been lost, and had to be replaced.

This week, the beautifully rich landscape painting with its elaborate gilded frame has been returned to display for the first time in decades.