Written with the body

No practice. No rubbing out. And don’t spill anything.

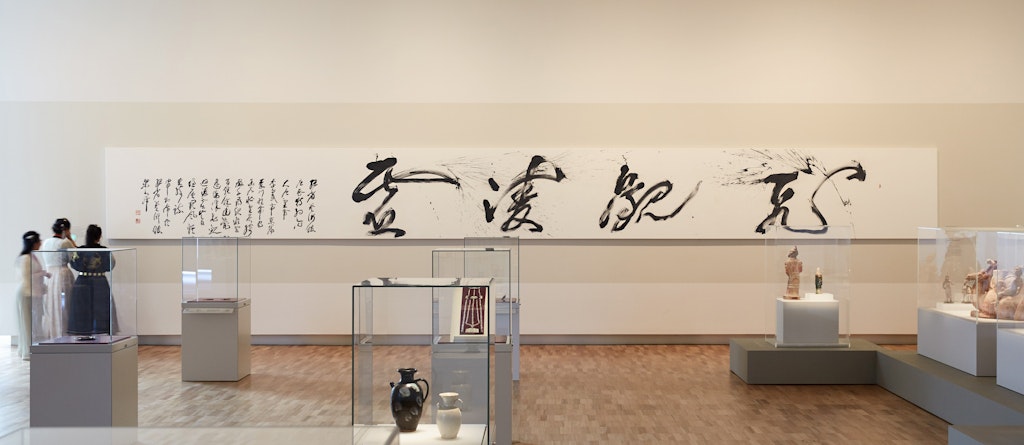

These were some of the challenges artist Liang Xiao Ping faced recently when writing calligraphy in acrylic and Chinese ink across an 11-metre length of stretched canvas in the Art Gallery of NSW.

‘You don’t have enough time to think about it. It’s spontaneous,’ Xiao Ping says of the largest commission she has ever undertaken, which is on display in the upper Asian gallery during the exhibition Tang 唐: treasures from the Silk Road capital.

The characters are a poem written by Tang Emperor Taizong (598–649) about his grand capital, Chang’an, present-day Xi’an, where the more than 130 objects on display in Tang were uncovered between the 1950s and the 2000s.

It was the first of 10 poems he wrote about the imperial capital. The four large characters in Xiao Ping’s calligraphy are a line that reads: ‘soaring belvederes remotely pierce the void’. The full poem is:

The streams of Ch’in lend grandeur to the imperial residence,

Han Vale lends might to the august dwelling.

Ornate halls rise a thousand yards,

Touring palaces, a hundred spans and more.

Interlocking tiles distantly touch the Han on high;

Soaring belvederes remotely pierce the void.

Clouds and sun ar ehidden in the storied gatetowers;

Wind and mist emerge from the figured tracery.

Liang Xiao Ping's calligraphy installed in Tang

Of all the traditional arts of China, calligraphy is the most esteemed and it was in the Tang era that calligraphy and poetry first flourished.

‘Master Liang’s work is very contemporary, but deeply rooted in traditional Chinese calligraphy,’ says the exhibition’s curator Yin Cao.

‘Calligraphy is based on yin and yang,’ Xiao Ping says, pointing out the variations within a single brushstroke. ‘Straight and curved … fast and slow … dark and light … space and solid.’

To work at this scale, Xiao Ping says she had to ‘use something like tai chi, harnessing the energy of the body’ to achieve the shifts in direction, intensity and speed the writing of each character required.

A prodigy who started learning calligraphy aged 5, Xiao Ping moved to Australia as an adult in 1987.

‘When I came to Australia, no matter how good you were at calligraphy, no one could understand you,’ she says. ‘I tried to think about how to help Western people understand. I thought, “Calligraphy is a beautiful pattern”.’

Her style has since been described as ‘painting within calligraphy, calligraphy within painting’. A hanging scroll by Xiao Ping entered the Gallery’s collection in 1996, while her work also graces the cover and title page of the Tang exhibition catalogue.

‘In China, with people using computers, calligraphy is dying,’ Yin says. ‘Liang not only continues the tradition but also evolves it into another stage. Now when you take it back to China, it’s still very unique.’

Watch a video of Xiao Ping writing the Tang poem in the Gallery.

A version of this article first appeared in Look – the Gallery’s members magazine