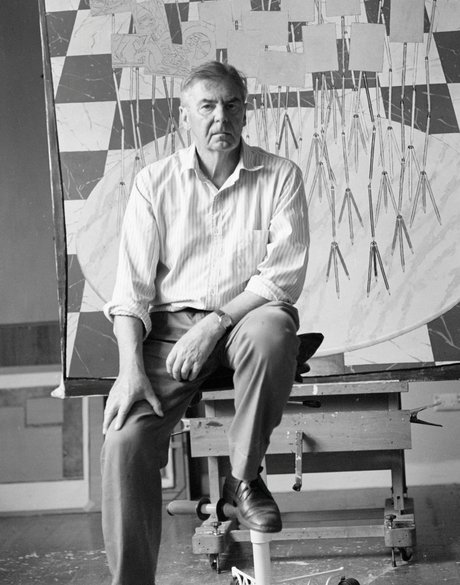

John Brack

Australia

Born: Melbourne, Victoria, Australia 1920

Died: Melbourne, Victoria, Australia 11 Feb 1999

Biography

A realist painter of modern urban life, John Brack emerged during the 1950s in Melbourne as an artist of singular originality and independence. His highly cerebral, smooth and hard-edged painting style was unique in the context of both the expressive figuration of Melbourne contemporaries such as Arthur Boyd and Albert Tucker, and the rapid growth of abstraction in his time.

After leaving school at 16, Brack worked as an insurance clerk in Melbourne when he was prompted to study art after seeing reproductions of work by Vincent van Gogh. He enrolled in evening drawing classes with Charles Wheeler at the National Gallery of Victoria from 1938 to 1940, continuing his studies full-time from 1946 to 1949 with William Dargie, after a formative period in the army. Employed from 1950 to 1952 in the National Gallery of Victoria’s print room, Brack went on to earn his living as a teacher for twenty years, eventually becoming art master at Melbourne Grammar School and, later, head of the National Gallery School from 1962 to 1968.

In his painting, Brack took as his principal subject the people and life of Melbourne, establishing a reputation for rigorously crafted insights into the complexities of urban and suburban society and consumerism. Widely read, his interest in the human condition was informed by writers including TS Eliot, WH Auden and Jean-Paul Sartre, and influenced in particular by the ideas of Henry James, who stressed humanist themes, humour and irony. George Seurat’s fusion of images of the passing world into a classical structure was also an early influence on his approach.

Depicting Australian culture during the Menzies era, where the home was viewed as the foundation of the Australian way of life, The new house 1953 portrays a conventional married couple – suburban homeowners – standing in front of their fireplace in a simply adorned interior. A reproduction of van Gogh’s Langlois Bridge 1888 hangs above the mantelpiece, while beneath it a small clock marks the time. The white apron worn by the woman, indicative of her domestic duties, suggests that lunch has just concluded. Tightly composed on a narrow vertical canvas with a precise arrangement of colour, the work is pervaded by a sense of flatness enhanced by Brack’s smooth application of paint which emphasises the clean, sparse qualities of the room.

The telephone box 1954, which depicts a woman mid-conversation on the telephone, is defined by a similar spare, geometric clarity with the central figure constructed through a series of repeated angular forms that echo the hard lines of her city surrounds. While conversations normally imply connections between people, this work presents the act of communication as strained and isolating.

Indicative of the powerful statements about urban experience that Brack exhibited in his initial solo shows in 1953 and 1955, the painting illustrates the artist’s strategy of drawing viewers into his work by positioning them as direct and close observers of his subjects rendered in acid sharp colour.

Delivering forthright social commentary both satirical and sympathetic, Brack’s paintings characteristically bear witness to the depersonalisation wrought by ritual. In particular the confined conditions of urban living gave him crucial insights into the loss of individuality revealed in in his stark evocation of city rush-hour crowds in The bar 1954 (an austere appropriation of Édouard Manet’s A bar at the Folies-Bergère 1882) and Collins St, 5pm 1955, both in the National Gallery of Victoria.

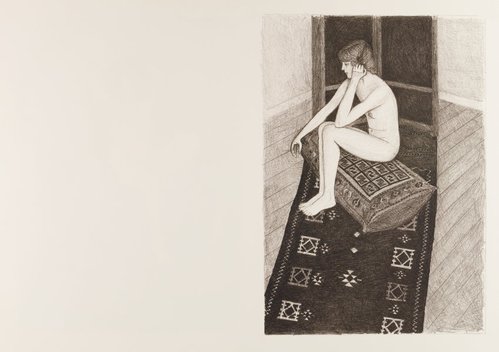

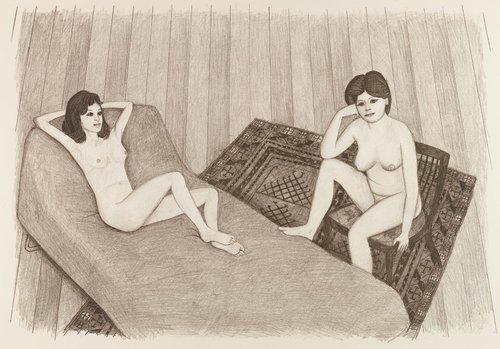

The subjects of his paintings range from weddings, ballroom dancers and gymnasts to shop window displays and starkly confronting nudes, exemplified in Nude with two chairs 1957, part of a series that was first exhibited in Melbourne in 1957. Contrary to the traditions of Western art, this work presents the nude as sexless and alienated from the viewer. The impersonal nature of Brack’s nude is heightened by the stylisation of the figure, which reduces individual features to classically architectonic forms. Nonetheless, Brack viewed his subject with sympathy, understanding and compassion:

When I paint a woman … I am not interested in how she looks sitting in the studio, but in how she looks at all times, in all lights, what she looked like before and what she is going to look like, what she thinks, hopes, believes and dreams.

In 1963 Brack began a series of paintings, the so-called 'surgical series’, which feature images of artificial limbs, surgical tools and related objects, inspired by commercial displays of a Melbourne surgical supplier. He made four etchings based on this theme in 1966, including Mirrors and scissors 1966, having first experimented with etchings and drypoint at Swinburne Technical College, Melbourne, in 1954.

Retiring in 1968 to concentrate on his art practice, Brack completed the satirical masterpiece Barry Humphries in the character of Mrs Everage 1969, which was a finalist in the 1969 Archibald Prize and was acquired by the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1975. During the late 1970s and 1980s his work became increasingly symbolic, featuring squads of pens and pencils as symbols of human conflict. Throughout his career, Brack lectured and wrote widely on modern art.