Robert Klippel

Australia, United States of America

Born: Potts Point, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia 19 Jun 1920

Died: Sydney, New South Wales, Australia 19 Jun 2001

Robert Klippel in his studio, 1963, by Robert Walker © Estate of Robert Walker. Source: Art Gallery of New South Wales Archive

Biography

Regarded as Australia’s leading sculptor, Robert Klippel consistently developed a distinct personal language of sculptural forms over his long career. Approaching the surface of each work as a logical expression of its interior structure and processes, his ambition was to make sculpture inspired by a poetic synthesis between the twin energies – organic and mechanical – that he saw as defining life and culture in the 20th century.

An experienced sailor and veteran of naval service during the Second World War, Klippel became a model maker at the Navy Gunnery in 1943. With little in the way of a formal art background, he began a sculpture course at East Sydney Technical College the following year, exploring the figure through life drawing, modeling in clay, and carving in stone and wood.

In 1947, Klippel left Australia for London where he studied at the Slade School. In London he met the Australian surrealist painter James Gleeson and the two collaborated on a figurative carving, No 35 Madame Sophie Sesostoris (a Pre-Raphaelite satire) 1947-48, one of the most successful artistic collaborations in 20th-century Australian art. Titled after TS Eliot’s ‘famous clairvoyant’ in The waste land, ‘Madame Sophie’ is a surrealist jewel that emerges from her wooden chrysalis to reveal the dazzling whir of an organic machine pulsing within. A gateway figure in Klippel’s art, she heralds the fantastic realm of forms in the unconscious and represents the culmination of the early, figurative phase of his practice that would give way to abstraction in the 1950s. In this work Klippel began the principal quest of his European years ‘to seek the inter-relationship between the cogwheel and the bud’.

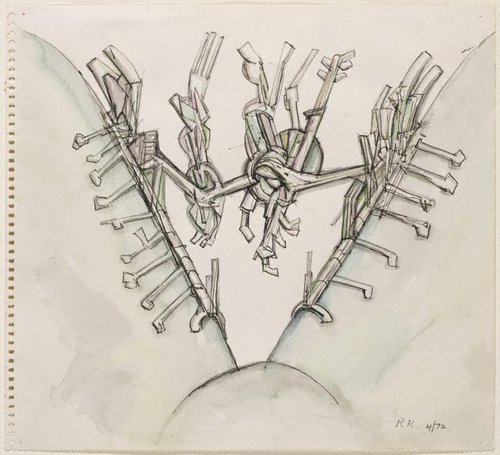

At the end of 1948 Klippel and Gleeson arrived in Paris, the ‘dream city of surrealism’, where they met André Breton and other French surrealists back from New York after the war. Klippel began experimenting with a modified form of surrealist automatism that imbued his abstract geometries with a nervy unpredictability. These ‘anatomies of sculptural energy’ took two forms: abstract expressionist ‘space-frame’ drawings and ‘tension-construction’ sculptures.

Returning to Sydney in 1950, Klippel mixed with abstract artists, exhibiting with William Rose, John Olsen, John Passmore and Eric Smith in Direction I in 1956. He acquired new skills through a series of night courses in arc welding, silver soldering and panel beating. Metals allowed Klippel to soar into space in ways that earth-bound wooden structures could not sustain.

In 1957, Klippel moved to New York and rented a studio from his friend, the assemblage artist Richard Stankiewicz. Alerted to the accidental but unlimited vocabulary of shapes available in junk metals, he began to create rigorously abstract yet metaphorically ‘alive’ assemblages of spiky and bristling forms from mundane materials such as typewriter parts, sending 19 back to Sydney for an exhibition at the Clune Gallery.

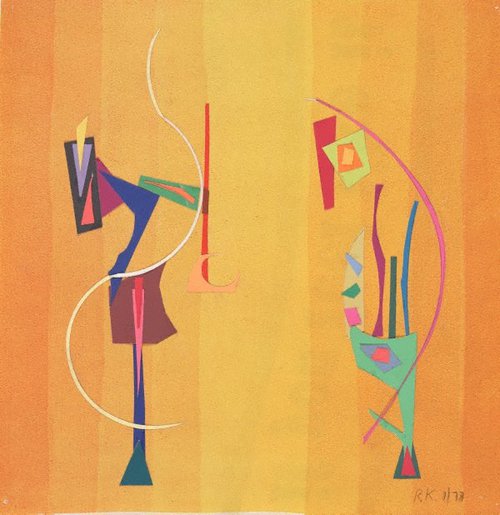

The success of the exhibition prompted Klippel’s return to Sydney in 1963 where he continued to work with junk machine parts unmoved by the advent of minimal and conceptual trends in sculpture. Experimenting with bronze in the late 1960s led to greater scale and simplicity in his work, and he began to employ wood, plastic and metal to create both monumental and miniature sculptures. The linking theme of work of this era was ‘sculpture-in-the-landscape’, which referenced both human scale and nature, revealed in his No 202 Metal Construction 1966 in which welded steel and found objects are synthesised into a resolved sculptural form that hovers between the organic and the mechanical.

For the last three decades of his life, Klippel worked out of separate studio-rooms in his harbourside home in the suburb of Birchgrove, engaging in the different activities of drawing, collage, welding, woodwork, clay modeling and plastic assemblage that responded to the creative principles he had established decades earlier.

His last significant series, including massive assemblages such as No 714 Wooden prototype for Adelaide Plaza bronze 1988, utilised discarded wooden patterns for machine parts discovered in an industrial foundry in Ultimo. Evolving out of Klippel’s earlier experiments with photographic collages, such as Philadelphia 1978-79 which was composed of images taken from a 19th-century book of drawings of machine parts, No 714 displays an apparently random yet perfectly balanced composition of dramatic colour, space and solid frontality in which the relationships of the static forms create an organic energy.

Robert Klippel’s archive is held in the Art Gallery of NSW’s National Art Archive.