The sublime is now

Focus work

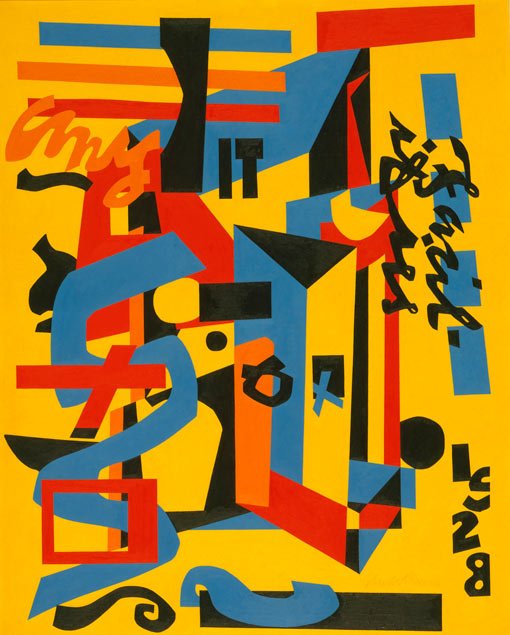

Stuart Davis

Something on the eight ball 1953–54

Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with the Adele Haas Turner and Beatrice Pastorius Turner Memorial Fund 1954 © Stuart Davis. VAGA, Licensed by Viscopy

Stuart Davis enjoyed inventive, modern language; the title of this painting sounds like jazz slang. His word-play humorously chides critics who thought that abstract art was easy; ‘facilities’, on the right margin of the painting, can be sounded out as ‘facile it is’. Davis often used the word ‘any’, as in the upper left corner, to declare that in abstract art any subject was as good as another.

Words were also energetic graphic elements that knitted together his abstract paintings. Davis sought a path between realism and pure abstraction. His paintings suggest modern urban and commercial environments. But they also emerge from his theories of colour and structure; the central geometric forms of this composition are based on folded match books, a common motif in his paintings of the 1920s.

Issues for discussion

Discuss the effect of using text and visual imagery in this painting. How does Stuart’s word-play add meaning to the work? Create a work of your own that uses word-play and imagery that reflects the times in which we live.

Artist biography

Stuart Davis’s career follows a remarkable path through the history of America’s twentieth-century avant-garde, with links to prominent artists and groundbreaking exhibitions as well as to modern movements in music, design and popular culture. Between 1909 and 1912, Davis studied at the New York School of Art with Robert Henri, the prominent spokesman of The Eight, a modern art group whose interest in urban life saw them dubbed the Ashcan School. In 1913 Davis exhibited in the Armory Show, a controversial display of European modernism that introduced Americans to avant-garde art and garnered world-wide attention. In the 1920s Davis developed a distinctive fusion of synthetic cubism and modern American commercial culture. Combining the flat geometry of cubism with the languages of advertising, packaging and street signage, Davis established a unique dialogue between the formal rigour of abstraction and the vibrant energy of modern life. He frequently linked the rhythmic energy of his paintings with jazz music. Decades later, he would be recognised as a significant forerunner of pop art. Davis’s activities in the 1930s placed him at the heart of the American avant-garde. He became politically engaged, joining the Artists Union and serving as national secretary of the anti-fascist American Artists’ Congress. Teaching at the Art Students League in the 1930s and the New School for Social Research in the 1940s, Davis guided an emerging generation of artists. He was a forthright proponent of modern art and of the Federal Arts Project of the Works Progress Administration. It is a measure of Davis’s impact on American modernism that, in 1957, when the New York Times asked American museum directors to nominate the artists whose work would endure, his name was given most often.