Into the abstract

From 4 November 2023 to 10 March 2024, the Art Gallery of New South Wales presents 47 paintings by Vasily Kandinsky drawn from the collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, curated by Megan Fontanella and Art Gallery curator of exhibitions Jackie Dunn. More so than any other artist, Kandinsky is intertwined with the Guggenheim Museum’s history and numerous works by the artist formed part of the core collection of the institution when it opened in 1939.

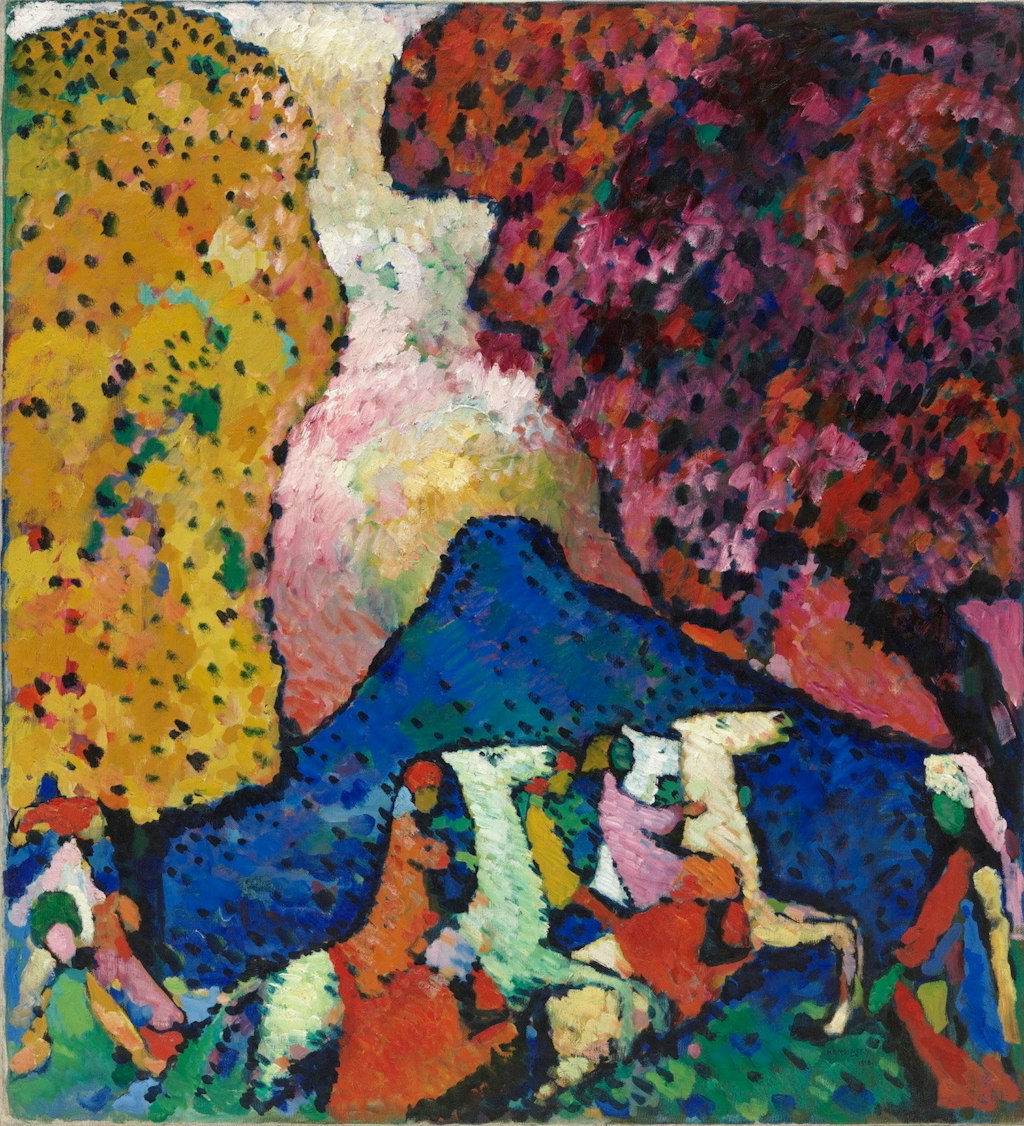

Vasily Kandinsky Landscape with rain January 1913, oil on canvas, 70.5 x 78.4 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, photo courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Vasily Kandinsky Landscape with rain January 1913, oil on canvas, 70.5 x 78.4 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, photo courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

In the opening decades of the 20th century, Vasily Kandinsky (1866–1944) was among those who advanced non-representational modes of art-making to lasting effect. The artist’s stylistic evolution in this regard was intimately tied to his sense of place and the communities with which he engaged. Kandinsky hardly ever worked in isolation. On the contrary, he gained insight from his meaningful intersections with an array of artists, musicians, poets and other cultural producers, especially those who shared his transnational vision and experimental bent.

Uprooted time and again, Kandinsky adapted with his every relocation across Germany, back to his native Russia, and eventually to France – all against the backdrop of the sociopolitical upheavals occurring around him. Ultimately his was not a fixed path from representation to abstraction, but a circular passage traversing persistent themes centred around the pursuit of one dominant ideal: the impulse for spiritual expression. This, what Kandinsky called the artist’s ‘inner necessity’, remained the guiding principle through the periodic redefinitions of his life and work.

The arts were ever present in Kandinsky’s upbringing, even if his decision to pursue such a profession was circuitous. He spent his youth in his birthplace of Moscow and in Odessa, Russia (now Odesa, Ukraine), studying law and economics at university before changing course in 1895 to become a printing house manager. A year later his encounter with one of Claude Monet’s Haystacks (Les meules 1890–91), as well as a performance of Richard Wagner’s opera Lohengrin 1850, inspired his full commitment to the arts and his move to Munich, a nexus of vanguard activity. Memories of Russia, such as brightly decorated furniture and votive pictures from the homes of the communities he had visited as a self-professed ethnographer in 1889, would define Kandinsky’s early work and resurface throughout his career, as would romantic historicism, lyric poetry, folklore, fantasy and other subjects of his youth.

Kandinsky’s earliest artworks were made while he was living in or around Munich from 1896 to 1914. This period was tremendously fertile for the artist. He quickly abandoned classroom instruction to work outdoors, painting on small-format, portable boards or canvases. His works from this developmental phase demonstrate a neoimpressionist style of dappled brushwork.

From around 1904 to 1908 Kandinsky traveled widely with his partner, the German artist Gabriele Münter, spending their time in the Netherlands, Italy and Tunisia, which was then a French protectorate. Kandinsky’s independent wealth sustained the artist-couple’s itinerant lifestyle, which was prompted in part by his desire for distance from his marriage to his first wife, Anja. He and Münter followed well-trodden itineraries and typified the bourgeois fascination with what they perceived as ‘picturesque’ or simpler ways of life in colonised lands, in contrast with their urban vantage point.

Kandinsky and Münter spent a year in Paris, in 1906–07. The daring use of non-naturalistic and vibrant colours in the paintings of the so-called fauves (or ‘wild beasts’) further influenced Kandinsky’s shift to magical fairytale pictures painted in a decorative art nouveau style. Russian folk costumes and themes also made their way into his work and, for a time, he turned to printmaking as a primary medium.

Vasily Kandinsky Blue mountain 1908–09, oil on canvas, 107.3 x 97.6 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, by gift, photo courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Vasily Kandinsky Blue mountain 1908–09, oil on canvas, 107.3 x 97.6 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, by gift, photo courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

In June 1908 the pair rejoined the artistic community in Munich, armed with the visual acuity they had gained during their years abroad. Kandinsky participated in heightened vanguard activity across multiple disciplines, fluidly moving between painting, poetry and stage composition, and engaging with the traditional decorative arts and cultural practices of the Bavarian countryside. He steered leading avant-garde groups, including Neue Künstlervereinigung München (New Artists’ Association of Munich), and his poetry as well as his groundbreaking treatise Über das Geistige in der Kunst (On the spiritual in art) were published. Notably, in 1911 Kandinsky and the German artist Franz Marc formed Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), a loose and transnational confederation of artists, writers and musicians united by an interest in the expressive potential of colour and the symbolic – often spiritual – resonance of forms.

Early pastoral landscapes and cataclysmic scenes emerged from Kandinsky’s dissatisfaction with urban industrialisation and perceived materialism. But by 1913 his recurrent motifs – among them the horse and rider, rolling hills, towers and trees – had become secondary to line and colour. Though he was not the first to experiment with abstraction, either among his European modernist peers or within its long history in diverse world cultures, Kandinsky’s intrepid work marked a broader shift toward non-representational art, which proved to have an enduring impact.

Vasily Kandinsky Improvisation 28 (second version) 1912, oil on canvas, 112.6 x 162.5 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, by gift, photo courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Vasily Kandinsky Improvisation 28 (second version) 1912, oil on canvas, 112.6 x 162.5 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, by gift, photo courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 compelled the artist, as a Russian citizen, to leave Germany and suspend his fruitful relationships there. The artist described the devastating displacement in a letter to his Berlin dealer Herwarth Walden, writing, ‘I feel as if torn from a dream. Within myself, I was living in a time when such things would be impossible. My illusion was taken from me. Mountains of corpses, all kinds of dreadful torments, spiritual culture wound back for an indefinite time.’

Eventually returning to Moscow, Kandinsky initially focused on watercolours and drawings to explore his creative instinct and perhaps make sense of his new reality. The October Revolution of 1917 in Russia tempered his impulse to resume painting on canvas and at larger scales and eliminated his financial security due to the Bolshevik expropriation of his real estate holdings. With his artistic output stalled, Kandinsky attempted to regain his footing through appointments to various political and cultural entities. In this context he closely observed the work of Russian and Ukrainian avant-gardists who emphasised the technical and scientific. While Kandinsky adopted their geometric vocabulary, he maintained his commitment to spiritual expression and to intuition.

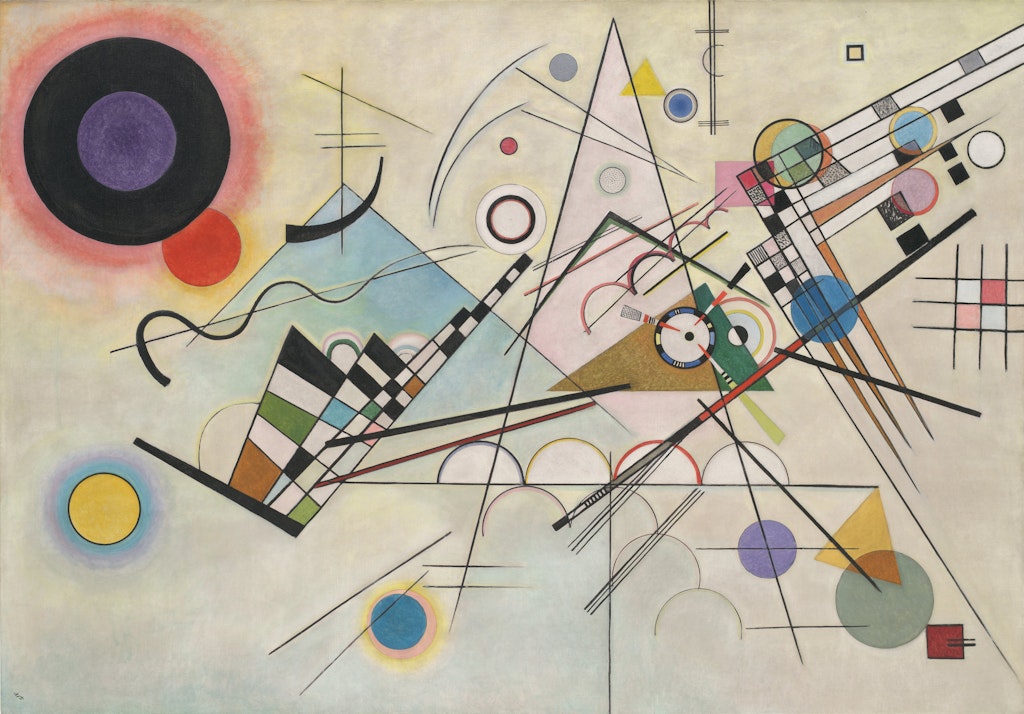

Marrying Nina Andreevskaya in 1917, the Kandinskys returned to Germany in 1922 and the artist began teaching at the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (and, later, its locations in Dessau and Berlin). Established by the architect Walter Gropius, this progressive school endeavoured to bridge fine and applied art – and, later, art and technology. Kandinsky taught mural and then easel painting, along with analytical drawing, and delved further into the correspondence between colours and forms and their psychological and spiritual effects, theorising these associations as general artistic principles. He especially seized upon the circle as a signifier for the cosmic realm, and as evocative of balance and harmony. Kandinsky’s body of work from this period manifests his conviction that art could transform self and society.

Vasily Kandinsky Composition 8 July 1923, oil on canvas, 140.3 x 200.7 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, by gift, photo courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

In the summer of 1930, Kandinsky received a consequential visit in Dessau from Solomon R. Guggenheim, who purchased his monumental Composition 8 from 1923. The US industrialist and future museum founder had begun acquiring Kandinsky’s work only one year before at the urging of his art advisor, the German artist Hilla Rebay. Guggenheim would ultimately amass more than 150 works by this single artist in his 20 years of collecting contemporary art. After Guggenheim established his eponymous foundation in New York in 1937, he opened the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (forerunner of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum) in 1939, and frequently showcased Kandinsky’s work.

Nina and Vasily Kandinsky remained at the Bauhaus until 1933, when the school was definitively closed due to pressure from the Nazi government. In his final chapter, set in France in the 1930s and early 1940s, the artist’s style shifted yet again while also surfacing long-held concerns. Kandinsky incorporated a soft palette of pastels and jewel tones, conjuring his early depictions of Russian and fairytale subjects and revealing little of the dejection surrounding his departure from Nazi Germany. Earlier, he had collected organic specimens and scientific encyclopedias; this interest intensified as he embraced imagery related to the natural sciences, such as botany, embryology and zoology. Contact with the art of Jean Arp and Joan Miró additionally impacted his intricate arrangements and biomorphic forms.

Vasily Kandinsky Around the circle May–August 1940, oil and enamel on canvas, 97.2 x 146.4 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, photo courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Vasily Kandinsky Around the circle May–August 1940, oil and enamel on canvas, 97.2 x 146.4 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, photo courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Many among the Parisian vanguard were familiar with alchemical, astrological and occult practices, in part given the literary and artistic pursuits of the surrealists, who aimed to unlock the unconscious and irrational mind. Against this backdrop Kandinsky’s own memories of his youthful encounters with the mystical reemerged and prompted themes of renewal and metamorphosis. As late as a 1937 interview discussing influential precedents, the artist recalled his 1889 field work in northern Russia, noting, ‘There, I saw farmhouses completely covered with painting – nonrepresentational – inside. Ornaments, furniture, crockery, everything painted. I had the impression I was stepping into painting that “narrated” nothing.’ He likewise sustained a preoccupation with the literature and belief systems of several Russian or Siberian cultures, including those with shamanic narratives involving transformation and ascendance.

By mid 1942, wartime shortages in occupied France led Kandinsky to cease painting on large canvases and instead make small-scale works on board and works on paper. His final group of inventive compositions exemplifies the personal iconography that recurred at every stage of his production. The artist died at home in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, in 1944. Solomon R. Guggenheim’s Museum of Non-Objective Painting organised a memorial exhibition the following year and, in the decades to come, would continue to interrogate the legacies of abstraction.

The 2023–24 exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales appears 41 years after a major Guggenheim-organised survey of Kandinsky’s work at the Art Gallery in 1982. Illustrating the full arc of his remarkable career, this year’s major exhibition provides a critical reexamination of a modernist innovator who was unwavering in his belief in the transformative power of art.

A version of this article first appeared in Look – the Gallery’s members magazine