-

Details

- Date

- 1977

- Media category

- Painting

- Materials used

- oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- 151.0 x 151.0 cm

- Signature & date

Signed and dated u.l. verso, orange felt tip pen "DENISE GREEN/ .../ 1977".

- Credit

- Gift of Robbie and Mary Rudkin 2008

- Location

- Not on display

- Accession number

- 260.2008

- Copyright

- © Denise Green/Copyright Agency

- Artist information

-

Denise Green

Works in the collection

- Share

-

-

About

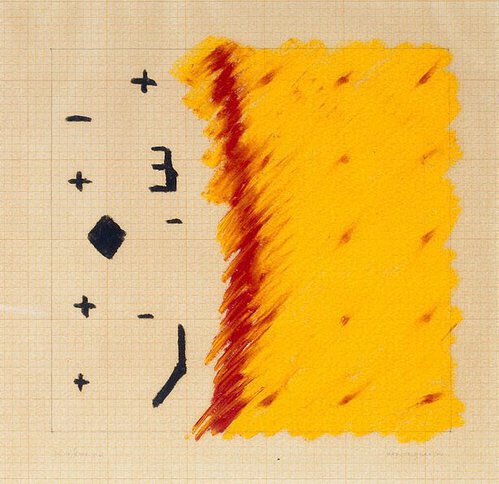

Denise Green first came to public attention through an exhibition, ‘New Image Painting’, at the Whitney Museum in New York in 1978. It was a time when the prevailing model for painting was abstraction while Minimalism and its successor Conceptual art dominated avant-garde practice. There was however a move towards new figuration along many parallel tracks including a return to gestural figuration, but more significantly a form of conceptual painting had emerged. The new conceptual painting was broadly identified as post-modern and took a critical view of painting traditions including the presence or aura that had been attributed to both abstract expressionism and Minimalism. Green’s painting was adopted into the more conceptual post-modern camp however with hind sight her outstanding achievement was to dig deeper into modernism and to embrace aspects of European painting since the renaissance.

Her work represents an apparent break with abstraction because she includes schematic images usually silhouettes of simple forms. On the other hand the paintings are overwhelmingly concerned with surface and mark making. It was a brave position or perhaps a naïve one within the context of Greenberg’s New York. Firstly American abstraction was seen as a break with European painting in as much as it eschewed any reference to the world beyond the frame. This literal understanding of art as autonomous even caused the Minimalists to be criticised by Michael Fried who saw that their work depended upon the viewer as an active participant and hence it was not perceived as suitably hermetic, it invited a theatrical response. Green’s paintings connect with the European tradition in which the hand of the artist seen in the paint surface brings about a similarly ‘theatrical’ engagement or bodily response on the part of the viewer. Her inclusion of icons, however schematic, refers back to the European history of iconography which is evident in Braque and even Picasso’s most fragmented analytic cubism pre 1912. None the less these are not representations of actual objects they are more the idea of a thing lightly hinted at.

Taken out of the context of an American turf war with Europe the purist Greenbergian position makes little sense since the human psyche does not allow us to see anything as autonomous even the most severe abstraction immediately begins to fill with associations. Minimalism was never affect free either; a wall of steel by Serra is always referential and impacts powerfully on our spatial sense and our anxieties about gravity. Even the accidental and uneven colouration of corten steel engages an aesthetic response and lends itself to our speculation on the history of the steel brought about by chance events that have made it the way is appears to us.

Similarly the surfaces of Green’s paintings have subtle but engaging qualities that affect us at a bodily level. The images within her paintings and drawings are never representations that would detract from our experience of this surface. They are close to hieroglyphics but they are too ambiguous to be literally read that way. They invite imaginative intervention on the part of a viewer; a fragment of a Brancusi column, the outline of a simple boat or punt, a silhouette of a classic vase are all things which may connect with our repertoire of stored memories. Because they are such “abstract” forms there is no particular place or object represented to derail, individual responses. Neither are these forms archetypal although it is tempting to think of them that way. It is more as if Green is trying to overcome the platonic problem of representation by stimulating the idea of a thing that is not contingent on specific time and space but exists only in the mind of the viewer.

‘Tulipidendron #1’ includes a generic trefoil shaped flower and a fan. Both fans and flowers occur regularly in her work. These ciphers sit on a field that has been animated by her method of application these are far from flat fields of colour, and the left half of the canvas is further articulated by a tight rhythm of evenly spaced horizontal lines. This grid suggests the musical connotations that also occur in the work of Agnes Martin. Martin creates subtle grids whose apparent emptiness acts as a calm still space for meditation; Green’s paintings aspire to a similar condition. The rhythm of the lines on this painting allude to time passing while the forms of flower and fan float outside of that progression suspended in a timeless space.

The lines could also be read as an open text. In some of her early paintings she introduces calligraphy suggestive of shorthand but not literally readable. The effect is somewhat like that of the numbers and letters in some of Jasper Johns’ paintings that engage our attention but can never be read literally. In both cases we are returned to contemplation of the transformation of base material (mud and oil) into something mysterious and poetic. Ian Burn wrote of the Johns’ paintings that the numbers encourage us to look for meaning but eventually the content eludes us leaving us with an awareness of the self reflexive process of looking at looking.

-

Exhibition history

Shown in 2 exhibitions

Denise Green. Affinities with Joseph Beuys, before and after Sep 11. A retrospective., Stiftung Saarlandischer Kulturbesitz, , 07 Sep 2003–19 Oct 2003

Denise Green, Museum Kurhaus Kleve, , 28 May 2006–03 Sep 2006

-

Bibliography

Referenced in 2 publications

-

Roland Mönig, Denise Green, 2006, (colour illus.).

-

Ernest W Uthemann, Denise Green. Affinities with Joseph Beuys, before and after Sep 11. A retrospective, 2003, (colour illus.). cat.no.56

-